By Spahic Omer

In 1909, photography as an art and utility was in its infancy, whose beginnings dated back to the first half of the earlier (19th) century. By all means it was a signature product of modernity. As it was to be expected, since Islam unequivocally prohibits taswir (producing pictures and drawings of living things, statues and idols), photography had a hard time penetrating the arena of Islamdom and gaining currency there. The pull of photography was remarkable, almost uncontainable, having scholars scratching their heads for a right answer. Debates were heated and endless, extending as inconclusive disagreements well into present-day times. In point of fact, many scholars “ as well as members of general public “ still trade blows over the subject matter.

Eventually, the mainstream position was that photography, in principle, is permissible under certain conditions. In his authoritative book œThe Lawful and the Prohibited in Islam Yusuf al-Qaradawi clarified: œPhotographic pictures are basically permissible. They become haram (prohibited) only when the subject matter is haram, as, for example, in the case of idols, individuals who are revered either because of their religious or worldly status, especially the leaders of idolaters, Communists or other unbelievers, or immoral individuals such as actors and entertainers¦ If any kind of photograph is to be prohibited, the subject matter will be the determining factor. No Muslim would disagree concerning the prohibition of photographing subjects whose portrayal is against the beliefs, morals, and laws of Islam¦ Making and acquiring drawings or paintings of trees, lakes, ships, mountains, and landscapes of this sort is permitted. However, if they distract from worship or lead toward extravagant living, they are disapproved.

In support of his views, Yusuf al-Qaradawi cited the late Sheikh Muhammad Bakhit, the Egyptian jurist, who ruled œthat since the photograph merely captures the image of a real object through a camera, there is no reason for prohibition in this case. Prohibited pictures are those whose object is not present and which is originated by the artist whose intention is to imitate Allahs animal creation, and this does not apply to taking photographs with a camera.

It has to be mentioned that some of the first Muslim reformers and modernists, like Jamaluddin al-Afghani (d. 1897) and Muhammad Abduh (d. 1905), were of the first Muslim scholars to allow photography. It likewise comes as no surprise that they were the first Muslim scholars to be photographed. Their actions were allied with the principle of walking the talk, and conveyed the messages of audacity, good sense and realism. There is a picture that depicts Muhammad Abduh as a middle-aged man with a black beard, but there are also others that depict him as a white-bearded old man. Which implies that the visionary Muhammad Abduh permitted photography long before it became a common application among Muslims.

The case of Makkah and Madinah (the Hajj)

As far as the holy cities of Makkah and Madinah were concerned, the first person who took pictures was Muhammad Sadiq (d. 1902), an Egyptian army engineer and surveyor. He took the first pictures of Madinah and some of its blessed sites when he visited the city for the first time in 1861, and of Makkah and its holy places when he came for the hajj pilgrimage in 1880. He performed the hajj as the accompanying officer and treasurer of the Egyptian hajj caravan. In all, he visited the Hijaz and its holy cities at least five times, from 1861 to 1887. He later obtained regional and international recognition for his breakthroughs in the field of œMuslim photography.

As per Miraj Mirza et al. when in 1860 the queen regnant of Bhopal in India performed the hajj she had a photographic camera with her. However, she desisted from using it inside the holy cities and their holy sites due to the perceived inappropriateness of doing so. If however she photographed any facets of the holy cities of Makkah and Madinah, she would have been the first person to do that. She would have created a piece of history thus.

The second person to photograph Makkah was Christiaan Snouck Hurgronje (d. 1936), a Dutch orientalist and colonial administrator, who did so in 1884-1885 when he, disguised and pretending to be a Muslim, had an opportunity to visit and stay for a year in Arabia, about half the year in Makkah and half the year in Jeddah.

The third person to take photographs of the holy cities was al-Sayyid Abd al-Ghaffar b. Abd al-Rahman. He was a medical doctor, and as a photographer, was very active from 1885 to 1900. He was from Makkah, and so, was the first local photographer in history. Even before 1885, he was enthusiastic about photography, but when he met and befriended Christiaan Snouck Hurgronje in Makkah in 1885, his photography interest and activities were taken to a whole new level.

According to Alexandra Stock, the two men soon began collaborating with one another, and this meant everything from struggling with the heavy camera equipment to working on their negatives in a portable darkroom. When Christiaan Snouck Hurgronje was forced to abruptly leave Arabia for diplomatic reasons, he gifted his photography equipment to his Makkan acquaintance, al-Sayyid Abd al-Ghaffar b. Abd al-Rahman. The two colleagues remained in contact thereafter, and between 1986 and 1989 the latter took more than two hundred and fifty photographs of Makkah and its residents, as well as the first photographs of pilgrims participating in the hajj.

The next two individuals who played a big role in the development of photography in Makkah and Madinah “ and in the Muslim world at large – were Ibrahim Rifat Pasha (d. 1935) and Muhammad Afandi al-Saudi (d. 1955). The former was an Egyptian high military officer and the leader of the security guards (amir al-hajj) that accompanied the Egyptian hajj procession three times, in 1903, 1904 and 1908. The latter was an intermediate officer, or a civil servant, in the ministry of justice in Egypt. In 1904 and 1908 he as a treasurer also accompanied the Egyptian hajj caravan.

This means that the two men: Ibrahim Rifat Pasha and Muhammad Afandi al-Saudi, were together on hajj in 1904 and 1908 and were part of the same Egyptian hajj party. Both of them had cameras during the hajj and both of them took pictures. In fact, Muhammad Afandi al-Saudi, as a younger, less experienced and lower-ranked official, was under the protection of Ibrahim Rifat Pasha. He certainly needed guidance and help, thanks to a number of volatilities and out-and-out hazards associated back then with taking photographs. Muhammad Afandi al-Saudi might also have been something of an apprentice to Ibrahim Rifat Pasha.

All things considered, the two men were torchbearers as to the popularisation of photography amongst Muslims. They were colleagues and partners, so to speak, and above all, close friends. Their work “ and the work of other early Muslim photographers “ were unique, in that their pictures were natural and spoke for themselves. They signified true historical records and testimonies. Much like their authors, they were witnesses of times, places and circumstances. They were silently eloquent documents, oozing generously as much about milieus as about auras that had saturated them. This was in opposition to œthe more common and staged Orientalist scenes that were popular at the time.

Photography and the Muslim modernist thought

However, what appropriately stands out is the fact that the last two photographers were modernists, in the truest sense of the term, and stood for a product of the growing Muslim modernist thought whose epicentre was in Egypt. Thats why Farid Kioumgi and Robert Graham, the authors of the book œA Photographer on the Hajj, the Travels of Muhammad Afandi al-Saudi, state that Muhammad Afandi al-Saudi had been greatly influenced by the modernist political thought of Jamaluddin al-Afghani and the modernist religious and educational thought of Muhammad Abduh.

More to the point, when Muhammad Afandi al-Saudi embarked on his first hajj in 1904, Muhammad Abduh – who was the grand mufti of Egypt and who died the following year, i.e., in 1905 “ asked him to furnish him upon his return with comprehensive accounts of the religious history of all pilgrimage“related sites in Makkah and Madinah “ understandably including pictures. Faithful to his philosophy and life principles, Muhammad Abduh wished to make the most of the modern technologies and tools for the betterment of knowledge and of various interdisciplinary sciences.

Hence, no sooner had he performed the hajj and had returned to Egypt, than Muhammad Afandi al-Saudi visited Muhammad Abduh and briefed him about what he had managed to do. He shared with him some information he had collected and transcribed by a pencil, promising that the rest of the requested data (knowledge) will be available in a book he was working on. However, following the death of Muhammad Abduh shortly afterwards, Muhammad Afandi al-Saudi was saddened and felt that the main patron (al-rai al-raisi) of, and motivation for, the book had just gone. Most of all, Muhammad Afandi al-Saudi regarded Muhammad Abduh as his teacher (muallim and ustadh).

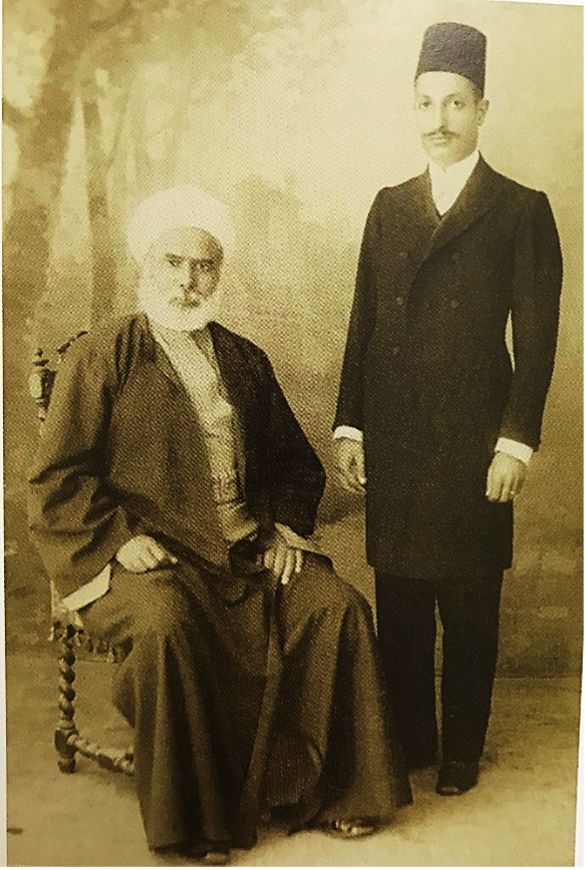

It is no wonder therefore that it was the youthful Muhammad Afandi al-Saudi who took some of the most iconic pictures of Jamaluddin al-Afghani and Muhammad Abduh. There is an emblematic photo in which he stands next to the seated grey-bearded Muhammad Abduh. The picture must have been taken either just before or after Muhammad Afandi al-Saudis first hajj trip. It was taken in a studio against a background featuring a blurred artificial landscape.

Nonetheless, things were not as smooth as one may think. As a new wonder, photography, more often than not, was condemned and disdained for various religious, political and cultural reasons. In the minds of many people, photography was verging on an illusion and a fragment of magic, with most other justifications for rejecting it simply bordering on the pointless and the ridiculous, casting light thereby on what exactly as insurmountable obstacles in terms of style, methodology and goals stood between sensible modernists and extreme traditionalists. And if the hajj was a perfect occasion for displaying this new technology and for getting breath-taking photos, it was also a perfect setting for laying open the other side of the coin.

At any rate, taking pictures during the hajj at the end of the 19th and the beginning of the 20th centuries was a dangerous exercise. It was an adventure fraught with perils. He who engaged in it was often bound to get more than he bargained for. He could never predict what was coming next, as Muhammad Afandi al-Saudi could bear witness. With most people harbouring doubts, mistrust and fears, the man went through loads of difficulties.

For instance, members of some Bedouin tribes accused Muhammad Afandi al-Saudi of stealing the souls and identities of photographed individuals; others believed that photographed persons, divested of spirit and essence, were destined to die soon afterwards; others thought that the photographer was a Christian performing the hajj in disguise, with the photography equipment and deeds being the main œclue; and yet some accused Muhammad Afandi al-Saudi of being a spy either for certain elements of the Ottoman government or for the interests of the British Empire.

Be that as it may, the context was precarious, and religious, together with political, zealots aplenty. The heavy hand of the law was practically outweighed by the heavier hand of religious fanaticism and political prejudice. Therefore, the young Muhammad Afandi al-Saudi must have been happy to have enjoyed the company and protection of the amir al-hajj, Ibrahim Rifat Pasha.

The experience of Arthur John Byng Wavell (1882-1916)

Wavell was a British military officer, Arabist and a fellow of the Royal Geographical Society. He secretly visited Makkah and Madinah as a disguised œpilgrim in 1908-9. His undertaking was ground-breaking, in that he arrived in Madinah via the historic Hijaz railway that had just become operational. His visit illustrated, and his narrative vividly documented, the onset of modernity in the holy cities.

Wavell œperformed his hajj (the hajj season commenced right at the beginning of January, 1909) one year after Ibrahim Rifat Pashas third and Muhammad Afandi al-Saudis second hajj in 1908. Wavell inherited and was a witness of the evolving Muslim culture of dealing with photography. In the process, he made some fascinating observations.

To begin with, Wavell said that he refrained from writing about the detailed information concerning the various points of interest especially in Makkah – albeit without discounting whatsoever the importance of those information. What he did, instead, was to purchase some relevant pictures at a bookshop in the vicinity of Makkahs holy mosque, inserting them later as an integral aspect of his hajj travelogue. Wavell did so trusting that œa good idea of the enormous crowd that gathers in the pilgrimage season may be gained from the illustrations, and that œthe photographs in this book give a much better idea of the place than any verbal description could do.

These Wavells words were rather avant-garde. They were reminiscent of the maxim œa picture is worth a thousand words. Since the origins of the maxim go back either to the end of the 19th or the start of the 20th centuries “ perhaps only several years before the publication of Wavells book “ one can, in part at least, come to terms with the amazing talent Wavell possessed. All things considered, though, he could be held as one of the maxims originators.

That pictures were openly sold in a bookshop near the holy mosque in Makkah demonstrates that photography had come a long way and was steadily gaining ground. The pictures in the market should have been produced by most, if not all, Muslim photography pioneers. One of them, certainly, was Muhammad Afandi al-Saudi. This is supported by the following. In the course of dwelling on the extent of some peoples religious small-mindedness and myopia – generally and during the hajj – which often led to outright acts of intolerance and aggression, Wavell said that it occasionally happened that Muslims of irreproachable antecedents had been accused of being disguised Christians. He then gave two examples.

First, œthe Turkish officer who took some of the photographs that appear in this (Wavells) book came near losing his life at the hands of some Magribi Arabs on the Day of Arafat. Second, there was œa Russian pilgrim who, though he was, and his family had been, Moslem for generations, was saved with difficulty by the Turkish authorities at Yembu from an angry crowd excited by a peculiar form of headgear he was wearing, which resembled a European hat.

œThe Turkish officer in the first example, in all probability, was Muhammad Afandi al-Saudi. Although Wavell did not provide a timeframe for the related incident, the same should have taken place either a year before (1908) or in 1904 when Muhammad Afandi al-Saudi was on his first hajj mission. Moreover, it was only Muhammad Afandi al-Saudi who explicitly wrote about incidents and maltreatments he had to endure while photographing the hajj scenes. A similar dimension is conspicuously missing elsewhere.

In his hajj travelogue – in connection with the hajj itself – Wavell used only three pictures: two portraying the cities of Makkah and Madinah respectively, and one illustrating the holy mosque in Makkah. These pictures Wavell bought in the Makkah bookshop. Most likely they had been taken by Muhammad Afandi al-Saudi, as they contained the hallmarks of his other pictures and of his overall style.

At the beginning of the book, furthermore, there is a full-body picture of Wavell wearing a traditional Arab dress. The picture was taken in 1908 in Damascus, when the author was in transit on the way to Madinah. Finally, Wavells book also features two pictures and two maps extra. They nevertheless pertain to his visit to Yemen, which came to pass immediately after the hajj.***