By Spahic Omer

(Contents: The book titled œYoung Islam on Trek: a Study in the Clash of Civilisations; Christian anti-Islamic polemics, islamophobia and the clash of civilisations; Basil Mathews on the Muslim world in the early 20th century; Makkah as a centre of pan-Islamism and anticolonialism; The secret of the hajj in loyalty to a man and a message; Attacking Prophet Muhammad; Attacking the Prophets message and legacy; Basil Mathews final missionary advice for Muslims and their youth; Only ecumenism and Christ could œsave Muslims; Conclusion)

Basil Mathews (1879-1951) was an English scholar born in Oxford and graduated from the citys famous University. His scholarly interests encompassed history, civilisation, anthropology, sociology, politics and religion. He was an example of interdisciplinary scholarship. In his early years, he even worked as a journalist and librarian, and during the First World War he worked for the Ministry of Information.

However, above all, he was a person of religion. He was a devout Christian. Most of his scholarly works were Christianity-centric, one way or another. Through the prism of religion he viewed all the other academic and real-world pursuits of his. All his works radiated the spirit of Christianity, ardently rationalising, expounding and propagandising it. He therefore was a scholarly missionary and his works in the service of direct and indirect evangelisation crusades. He might not have been a Christian missionary out in the field, but was a missionary to missionaries, or a trainer of trainers, so to speak. He might not have been a foot-soldier, but was one of the generals and masterminds of evangelism.

For many years Basil Mathews resided in London, where he served the British missionary societies as editor, writer and press representative. In 1924 he became Literature Secretary of the Boys Work Division of the Worlds Alliance of Young Mens Christian Associations, with headquarters at Geneva, Switzerland. During his five years in this post he edited Worlds Youth (a Christian periodical) and served the international missionary organisations in preparing an interpretative literature regarding the Christian movement in many parts of the world.

He was in favour of ecumenism which, as an idea and principle, advocated stronger unity and closer relationships between all Christians and their different churches or denominations (interdenominational strategy). He propagated the notions of universality, solidarity and humanity under the sole banner of Christ, so that all Christians may be one and all the world may know the Christian truth and hence, become also one. All his missionary thought and activism were coloured with this philosophy.

With the rapid rise of Western civilisation – coupled with the enterprises of colonisation and global westernisation – and with the correspondingly rapid decline of Islamic civilisation, which theretofore was the worlds most dominant civilisation, the whole world stood at a crossroads. Youth was at once most buoyant and aspiring, and most vulnerable. No wonder that they were prized “ and targeted “ most. For the enlightened and visionary they were a source of hope and assurance, but for the myopic and disoriented they were a source of distress.

Basil Mathews Christian persona and Christianity-inspired professional career are clearly manifested in his writings. He authored numerous books. At the beginning of his book œThe Church Takes Root in India, the publisher listed sixteen books and then just added œand others. Wikipedia enumerated 23 major publications. His books revolve around such pure Christian themes as the life of Jesus and the world in which he lived, Saint Paul of Tarsus and his life and Christianity mission, the City of God (De civitate Dei) and the roads that lead to it. He also wrote about world politics and conflicts, and about the world of Christianity in such a milieu, subtly relating burning issues and challenges to those confronting Christian missionaries and the future of Christianity. His favourite concept is œclash, to the point that it almost became a mantra, such as œthe clash of civilisations, œthe clash of colour (on racism), œthe clash of culture, œthe clash of race, œthe clash of world forces (on nationalism, bolshevism and Christianity) and œthe clash of values. However, books on missionary works and heroes tower above all others, featuring various missionary heroes and missionary works in India, Africa, œNearer Asia and in the Muslim world.

Perhaps the following four titles encapsulate Basil Mathews fascinations, direction and compass: œDisciples of All Nations, œEast and West: Conflict or Cooperation, œShaping the Future: a Study in World Revolution and œFellowship in Thought and Prayer. As do the following words extracted from a hymn œFar round the world thy children sing their song composed by the same author and which was published in Church Hymnary in 1927: œFar round the world thy children sing their song; From East and West their voices sweetly blend; Still there are lands where none have seen thy face; Children whose hearts have never shared thy joy; Yet thou wouldst pour on these thy radiant grace; Give thy glad strength to every girl and boy.

The book titled œYoung Islam on Trek: a Study in the Clash of Civilisations

One of the most intriguing books of Basil Mathews, positively, is œYoung Islam on Trek: a Study in the Clash of Civilisations. The book was published in 1928 by Church Missionary Society in London. It is based on the authors theoretical and experiential knowledge of Islam and Muslim, the latter having been acquired especially in 1914 and 1924 when Basil Mathews traversed much of the Muslim world. In line with the authors overall philosophy and scholarly trajectory, this book, too, was written about religion, evangelisation, politics and the future prospects of the world, with Islam and its youth “ against the backdrop of the mounting predicaments of Islamic culture and civilisation – as a focus.

The author explicitly states that the book œis written for youth about youth. He meant thereby youth in general – for knowing the ongoing challenges of Islam and its current, together with future, generations was useful to help chart a homogenous ideological and civilisational mosaic of the global youth agenda – and Muslim youth in particular, because of all the movements of youth in the world, none surpassed the trek, or journey, of œyoung Islam. In the might of its momentum, the range of its flow, the depth of its significance, its contrast with the past and its influence on the future life of the world, œyoung Islam was of supreme importance and entrancing interest.

Furthermore, studying Islam as a whole since the turn of the 20th century in the West was paramount. To handle it completely, though, it was a subject for a whole library of books, œa matter for a life-study, for endless travel, for superb language-scholarship, for the eye and the pen of statesman, scholar, seer, prophet and literary genius in one. However, the myriad details and the astounding complexity notwithstanding, Basil Mathews affirmed that he tried his best to catch those great salient realities – pertaining to the people, the ideas and the movements – as presided over and dictated œthe moving human scene.

The author also admitted that in order to fulfil his task, he had been helped by experts œtoo numerous to detail. Which means that the book was a special ecumenical project and required special sacrifices and contributions from different parties. It was in the same series as the book œThe Clash of Colour, preceding it by one year. In both books, with intent, Islam and Muslims have been depicted as a main source of all sorts of œclashes. For instance, in the book œThe Clash of Colour, in the context of India, the author concluded: œThe new-comers now brought Islam and the Moslem brotherhood. They gave India its great permanent internal race-conflict of Hindu versus Moslem – a clash of race and of culture that is all the fiercer because it is also religious. It runs deeper than any other division in India.

Basil Mathews believed that, as a chief target of synchronised missionary efforts, the Muslim world could easily be transformed into a world of amazing opportunities and alluring prospects. The stunning dynamic scenes of the œcivilising march of Muslim youth and of the generic dramatic developments in the Muslim world could furthermore be turned into promising evangelisation spheres. Promoting the viability of the subject matter, and facilitating it somewhat, was the principal objective of the book œYoung Islam on Trek: a Study in the Clash of Civilisations.

Christian anti-Islamic polemics, islamophobia and the clash of civilisations

The additional significance of the said book lies in the fact that it clearly displayed the Western early-20th-century mentality towards Islam and Muslims. It validated the perennial and widespread misconceptions as well as bias. It showed that nothing essentially changed from medieval or middle ages when Christian radical anti-Islamic polemics were rife and state-sponsored. The trend was but intensified and expanded in subsequent times. So much so that it morphed into elements of outright islamophobia as a pandemic and was thus sealing the fate of Islam-West (Orient-Occident) relations.

If truth be told, the political wranglings and military conflicts between the two orbs were no more consequential than the intellectual and ideological ones. The solitary aim of the West was to conquer, colonise, control and exploit the Muslim world. Attempts to proselytise it – though extremely hard, as constantly proven “ was an option, too. If nothing, alienating Muslims from Islam and its culture as well as history – by whatever ideological and functional means and strategies, not only by such as were related to Christianity – was good enough. All the talk about peace, alliances, cooperation and coexistence was a smokescreen intended to conceal the real intentions, and a decoy aimed to throw many often-credulous Muslims off the trail.

Hence, to Basil Mathews, modern and pulsating Islam-West relations were nothing short of a clash of civilisations which assumed both internal (domestic) and external (international) dimensions. As a result, for example, if the ongoing all-purpose conflicts between Islam and the West – where the spirit of backward tradition confronted the spirit of innovative progress – stood for a symptom of that type of clash, so did the fight of œhat versus œfez in Turkey signify a crucial battle in the same clash of civilisations.

The book signified a proof of, and a contribution to, the steady transition from anti-Islamic polemics to islamophobia, paving the way for the emergence of a clash “ real or illusory regardless – between Islamic and Western civilisations. Its author, it goes without saying, was not just a Christian scholar and missionary, who targeted among others the crisis-stricken world of Islam, but also an active participant in the spreading and sustaining the islamophobia scourge. He was a modern servant of such medieval giants of Christian apologetics and anti-Islamic polemics “ and by extension the pioneers and godfathers of islamophobia “ as John of Damascus (d. 749), Peter the Venerable (d. 1156), Riccoldo da Monte di Croce (d. 1320), Martin Luther (d. 1546), and many others.

Basil Mathews legacy was a continuation of the legacies of his predecessors. It yet supplemented and, most importantly, modernised them in agreement with his personal ecumenical penchant. Those were the stages of an evolution that was as dynamic as it was ceaseless. Indeed, the islamophobia of the late 20th and early 21st centuries owes as much to its medieval pioneers and godfathers as to its benefactors and advocates of early modern times, including Basil Mathews.

Firstly Christian radical anti-Islamic polemics and then islamophobia were the root causes of the purported clash of civilisations “ which was later picked up and taken to the next level in a global context by Samuel Huntington who identified the idea of the clash of civilisations, whereby generally peoples cultural and religious identities were set to become the main source of global conflicts, with the idea of the re-making of world order. Existing exclusively in the mind or, to some extent, even in real life “ or being simply a work of fiction “ the clash of civilisations feeds on the existence of islamophobia. Without it as the main cause, it cannot live on. Thus, whenever and wherever there is islamophobia, there must be a sense of a clash of civilisations as well, and vice versa. The latters subsistence and scale are commensurate with the subsistence and scale of the former.

Basil Mathews on the Muslim world in the early 20th century

From a Muslim perspective, Basil Mathews painted the gloomiest picture of the condition of Islam and Muslims in the early 20th century. The image however was fraught with inaccuracies, exaggerations and preconceptions. That was intentional nonetheless and was designed to exhibit to the Western world how vulnerable the Muslim world had become and how little threat it posed to the West, on the one hand, and how many missionary (evangelisation) opportunities the state of affairs entailed, on the other. More than ever before, the situation had come to be ripe and the stage set for unobstructed and so, productive missionary activities. As a publicity material, the image was further meant to dampen the spirits of Muslims and to stimulate the Westerners and rouse their missionary crusaders to action.

Basil Mathews set the tone of his exposition when he said that in the deserts and oases of Arabia and Sub-Saharan Africa nothing has practically changed in forty centuries. A scene of a caravan journey that one could witness at the outset of the 20th century on one of many desert ways was like a scene of the 7th century œwhen Mohammed in Arabia was rallying his tribes to capture Mecca. And “ omitting the tobacco and the prayers to Mecca “ the happenings and the scene were the same when the Sphinx was new and the Pyramids were innovations.

In this way, not only did Basil Mathews rule out any contemporary civilisational awareness and legacy of Muslims, but also did he preclude any such thing in the past. As if Muslims contributed nothing to the world civilisation-wise throughout their long history. The only thing they had and were able to offer were some absurd religious beliefs and practices “ implied by the words œthe prayers to Mecca “ and questionable lifestyles often given to pleasures and self-indulgences “ implied by the word œthe tobacco. However, even those œcontributions eventually grew into a source of worldwide antipathy and disdain. They became a stumbling block for a true cultural enlightenment and civilisational progress.

This cultural bareness and civilisational nothingness of Muslims were additionally accentuated when they were uninterruptedly stretched from the 20th century to as far as the epochs of the Sphinx and the Pyramids. Put in other words, Prophet Muhammad came and left, followed by the centuries of the spread and operational existence of Islam, but nothing really changed, nor improved whatsoever. No authentic civilisational footprint did any of those events and their protagonists leave in connection with a genuine refinement and enrichment of societies and lives. Muslims, it follows, were not civilisation-makers, but only civilisation-consumers and at times even civilisation-destroyers. They were but a footnote to the history of civilisation-making. Some nations from antiquity, like the Egyptians, were a lot better than them.

However, with the advent of Western peoples as colonisers to the primitive world of Islam, carrying the products and epitomising the spirit of Western cultural and civilisational proclivities, things and scenes were destined to change forever. They were never to be the same again, as the new ground-breaking events were unfolding and the new unmatched chapters were inscribed inside the story of mankind. The central characters were now Westerners as proponents of freedom, knowledge, invention, science and technology. There however was no place in the new chapters for proponents of regression and medievalism. Neither they nor their anachronistic and regressive thinking could be accommodated. The time of primitivism and barbarity was over; the future belonged to the new paradigm, which was grounded on a fusion of the novel Western civilisational outlook and its inherent Christian faith.

Naturally, upon the arrival of Westerners in the Muslim midst with their embedded dispositions, all kinds of clashes unavoidably ensued. Basil Mathews pinned them down as the spirit of tradition and of the old clashing with the spirit of innovation and of the new. He also envisioned the matter as the children of nature facing the new masters of natural forces, the latter in the end prevailing over and becoming the masters of the children of nature as well. In short, that sort of interaction spelled the quintessence of œthe clash of two (Islamic and Western) civilisations.

A sign of the clash was the contrast between camels still used as the prime mode of transportation and the œreeling masses of painted metal lurching over the desert at six times the pace of the camels, i.e., motor-cars. In passing, Basil Mathews had in mind and was referring to the Sahara and an occurrence which he himself had witnessed. The occurrence involved a camel caravan that was bound for Makkah as part of the hajj pilgrimage. A critical aspect of the mentioned sign was the state of the mind of the cameleers and all that concentration of inventive genius that the cars were representing and which stood for another œstate of mind. According to Basil Mathews: œThe cars say something new to those young Moslems (cameleers and members of a camel caravan). They sound a chord never struck before. They sing of command over the mighty forces of nature; they sing of power and speed, of adventure among new scenes, of the opening of fresh horizons, of the thrill of life in great cities.

Moreover, the cameleers and the members of the caravan, who represented different Muslim regions in Africa, gazed in bewildered wonder at the cars “ the Citroens as a French brand of automobiles introduced in 1919 – which had been made known to the Muslim reality via the French colonisation. They were spotted in the Sahara as part of the French active colonial presence. Basil Mathews continued his reflection to the effect that those Muslims watched the cars but were blind to the brilliance of the concentration of a thousand devices in the amazing effort to conquer the desert. They knew nothing of the myriad minds at work incessantly in the British Commonwealth, Europe and America, œstriving to blend steel and rubber, fibre and copper, petrol and electricity, into a perfect mechanism.

The Muslims in the caravan by no means could get to the bottom of what they had just witnessed, nor could they come to terms with what exactly was going on in the grand scheme of things civilisation-wise, but the impression generated thereby was profound and everlasting. It posed endless difficult questions for whose answering an entire lifecycle was needed. Indeed, the sensation must have been as open-endedly stupefying as the vastness of the Sahara Desert itself. Yet it would not be an exaggeration to say that it also was akin to a psychological bombshell and a form of rude awakening.

In Basil Mathews perspective, the desert scene was a microcosm of the Muslim reality. The car convoy and the camel caravan went their separate ways, but the spectacle brought home that both the Muslim mind (heart) and the Muslim way of life were increasingly intruded upon and challenged, and were becoming ever more restless. They were going out on a new trek “ willingly or unwillingly. However, the paths were not well-beaten and, while on them, it was unclear where, when and how much the measures of defiance, defence and isolation needed to be given up, and where, when and how much the measures of concession, conformity and toleration needed to be adopted and let take charge. The situation, certainly, connoted a grave conundrum, which was gradually turning into a full-blown crisis.

Basil Mathews further perceived “ and dramatised – the matter as follows. The young Islam was awakened and permanently set in motion on a new journey and towards a new direction. Whether the new odyssey was in the long run better or worse, nobody could confidently say. Such was as much a gamble as an adventure. But the die was cast, which is to say that the decision had been made and was irrevocable, albeit with little or no choice to contemplate other alternatives. The old ways were never to satisfy again the ambition of the young and future Islam.

The desert scene was “ Basil Mathews rationalised – œone small picture of the enthralling drama that is being played out under our eyes today in the wonder-lands of the Moslem world. It is a drama in which we, in whatever land we live, are all involved. For it is a drama in which every new force of the Western world is interlocked with every old impulse and habit of the East; a drama of the conflict of ancient ways with super-modern innovation; a drama half-tragedy, half-comedy. In that drama young Islam is being called to a new trek by voices never heard before – voices that will not be denied. It is still in its early scenes. The later acts are yet unwritten, and our generation cannot escape from the writing of them.

Basil Mathews went so far as to say that the mentioned sight of the Citroen expedition across the Sahara was also the symbol of a force that was disintegrating the old and traditional interpretation of Islam. It symbolised that a war of ideas, values and standards was raging across the Muslim world. The First World War had commenced in 1914 and had ended in 1918, affecting greatly the socio-political landscape of Muslims, but the ideological and cultural wars continued unabated. Their battles unfolded in every house, every mosque, every educational, religious and socio-politico-economic institution and establishment, and on every street. If in the formers military battles the life of every military and civilian person, and every inch of a territory, mattered, in the latters doctrinal and political battles the educational, spiritual and cultural wellbeing of every individual was targeted and thus, mattered most. In the physical military struggles of the entire 19th and early 20th centuries, the Muslim world was seriously wounded and was profusely bleeding. The concurrent – in addition to succeeding – ideological and psychological assaults were meant to seal its fate. They were planned to be the last nail in the coffin of an already foundering civilisational enterprise.

Consequently, Muslims became disoriented and confused. In terms of their physical presence, they were divided, weak and directionless, and in terms of their productive efficiency and inventive output, they were barren. They were a sterile and spent force on the global stage. Some of the most critical concepts that for centuries were defining Muslim endeavours and accomplishments – such as caliphate, the shariah (Islamic law), jihad (holy struggle including holy war), the role of women, the veil, Muslim brotherhood, Islamic education, ijtihad (independent reasoning), etc. “ were at stake. By way of illustration “ as per Basil Mathews understanding “ the feminism movements were set to change everything as far as Muslims were concerned. œFor to alter the life of woman under Islam is ultimately to transform Moslem civilisation in every atom of its body.

On account of all this, in tandem with the physical colonisation, nonmaterial forms of colonisation were taking place as well, adopting almost similar levels of urgency and intensity. Most of the segments that pertained to education and even acculturation were delegated to Christian missionaries. One however should not be deceived and start thinking that the aim was proselytisation per se, in that such a thing was extremely hard and could easily backfire if one considered the nature of the historical and theological relationships between Islam and Christianity and how the former was always projected “ and undeniably proven in thought and everyday life “ superior to the latter. Rather, the aim was to disconnect Muslims “ especially Islams youth “ from their beliefs and values, plus their history and culture. The vacuum thus created was to be filled with such Western-Christian values and outlooks as appeared innate, pure and universally acceptable, and were not in outright conflict with Islam. As a result of continuous indoctrination efforts, those values and attitudes, under the guise of humanism, universalism and greater good, were then expected to subtly start appearing as though innocent, progressive and irresistible.

Basil Mathews said about these strategies – in the context of Christian missionaries establishing educational colleges and other institutions across major Muslim cities – that œthe aim of these colleges is to give to the Moslem world what it supremely needs – young, courageous, well-equipped leadership with a Christian outlook on life. They aim at making these leaders not Western in mind, but good citizens of their own land.

Those schools and colleges “ indeed, in some cases fully fledged universities, such as the American University in Cairo which was founded in 1919 by American Mission in Egypt, a Protestant mission sponsored by the United Presbyterian Church of North America “ were not built by governments or members of business communities, œbut by the wise enthusiasm of Christian men and women in Europe and America. œYoung Islam – its girlhood as well as its manhood – is taught in these schools and colleges the newest discoveries of Western science in medicine, in dentistry, in engineering, along with the deepest (Western) philosophies of the world, and is shown how man was made by his Creator not for antagonism but for co-operation. They are taught this not only in the classroom, but through the spirit shown by the (Western-Christian) professors and tutors in the daily life of the place, and in the team play of football, net-ball, tennis, cricket and other sports of the West that are now, for the first time, being caught up with such enthusiasm by youth in the Moslem world.

Basil Mathews also disclosed, as part of his own discoveries while in Egypt, that the high Muslim officials in Egypt preferred to send their sons to the Christian (American) University in Cairo, in spite of the presence of the al-Azhar University, œthe central Moslem university of the world. The author remarked that the American University in Cairo was known as a Christian institution, albeit not controversially so. It was a proof of how the most conservative circles of Islam were coming into touch with the progressive teachings of Western science and even of Christianity. The main motive of those officials “ all elites – was the desire to give their sons equipment in mind and in character for a career in the world of tomorrow.

Additionally about the educational modi operandi at the American University in Cairo, Basil Mathews said that during studies, daily chapel (religious service) was required of all students “ Muslim and non-Muslim “ and two periods of religious (Christian) instruction each week. The approach was œsympathetic and œhumane. It aimed to equate education with the purpose of life, to instil a sense of responsibility, and to create capacity. Those were the supreme needs of Egyptians and all Muslims. The Muslim students were told: œThese are the things which we have found helpful in our own personal lives. We want to tell you about them. You can take them or you can leave them, as you wish. Basil Mathews concluded that the Muslim students were ready to listen to such œbenevolent and œnatural Christian teachings.

The mood was all-pervading. The same author said when he visited al-Azhar, œthe central intellectual citadel of historic Islam, he saw a cluster of students grouped on the pavement under the arcade around an atlas open at a double-page map of the world. He also noticed the presence of some French novels of the more lurid order, and that a student was reading a Christian Arabic pamphlet. To the author, all that stood for a symbol of the fact that for the first time in history the eyes of the Muslim world were turned, not in arrogant self-content, but with genuine inquisitiveness, upon the life of man all over the earth. It was furthermore a portent of the increasing flow of œthe secular and sceptical Western mentality into the Mohammedan peoples steeped in tradition and age-long habit. The youth of Islam were interested not only in the scientific and economic secretes of the West, but also in its faith.

The above tactics and programs were envisioned to be essentially long-term, even though some of their permutations might have appeared to be otherwise, serving as adequate solutions either on a short or a medium term basis. The actual results were not anticipated to be seen and their inclusive impacts felt except in the long term. The ultimate goal was to clear the way for avoiding the potential clashes of Western and Islamic civilisations “ albeit on the terms of the former – and to render the working, along with the spread, of Western civilisation both unilateral and unobstructed.

At the beginning of the 20th century, all those Western initiatives – exemplified by the creation of Christian missionary schools and colleges – almost alone among all the ferments and forces at work in the Muslim world did not make for a clash, but for a blending of civilisations. They were also alone that did not make œfor explosion and catastrophe, but for seed-sowing and growth and harvest. Thus, colonisation and occupation were attempted to be portrayed as progressive, while opposing them was regressive; capitulation and compliance were in furtherance of peace and diplomacy, while denunciation and resistance were but in the interest of intimidation and violence. In cases of colonisation catastrophes, the blame was ready to be cunningly shifted from perpetrators to victims. It was easy to put down all problems to the latters obstinate holding on to the old barbaric and primitive ways. It was propagandised that colonisation was pro-civilisation and in everybodys interest, whereas anticolonialism was in opposition to it and was counterproductive to everybodys ambitions.

The Muslim not only existential, but also intellectual and spiritual being was brought to the most critical juncture of its long history. It was baffled and torn asunder between the forces of tradition and modernity, old inertness and primitiveness and new dynamism and progress, and between desperation and hope. All the forces aimed specifically at its existence, vying for its endorsement and latent capacities. The painful truth was that eighty per cent of Muslims (totalling nearly two hundred and thirty-five million at the time) were under the rule or protection of Western governments. Some seventeen million were in semi-independent lands or in countries mandated under the League of Nations. A bare thirty million lived in independent Muslim states. That means that, approximately, out of every eight living Muslims, only one was under Muslim rule. The other seven were ruled by Western powers. Within the British Empire there were 105 million; Holland followed with 39 million, France had 23 million and Russia 15 million.

Although the situation was exceedingly depressing and gloomy, the vanquisher in the perceived clash of civilisations could still see the light at the end of the tunnel. It was owing to this that Basil Mathews was optimistic. He likewise was able to foresee that the ultimate outcome would be in favour of “ and as a form of return on – all the exertions and œinvestments of the West in general, and of Christian missionaries in particular. He was particularly driven by his ecumenical spirit and its precepts of universality, unity, inclusiveness and humanity. That, he anticipated, will tip the balance.

Basil Mathews thus elaborated: œCalls are coming to the youth of the Moslem world through all these varied modem channels. The picture palace and the newspaper, the motor-car, the train, and the ocean liner, the telephone and the sewing-machine, the cable and wireless; these strange movements of nationalism, feminism, Bolshevism and secularism, Western science and aggressive commerce – all are luring young Islam from the old camping grounds. The Mohammedan traditional life is losing its hold on millions. Many millions more, of course, of peasants and people in remote places are still unmoved. Many leaders among the old guard are calling Islam back to the old ways. The clamour of new voices calling in different directions is bewildering. There is no clear voice that can either hold them back or can lead them out on a definite trek to one goal. Wise and learned men have indeed said again and again that the East would never change and that Islam would never move. They can never repeat that again. For the change has begun; Islam does move. One by one, and group by group, young Islam is beginning to strike its tents and to move out on a new trek. But whither? Across what desert? Along what trail? Under what leadership? To what goal? It is the riddle set by the Sphinx of Time to our generation. And the legend has always said that, at some sudden sunrise, her lips will open and we shall hear the answer.

Makkah as a centre of pan-Islamism and anticolonialism

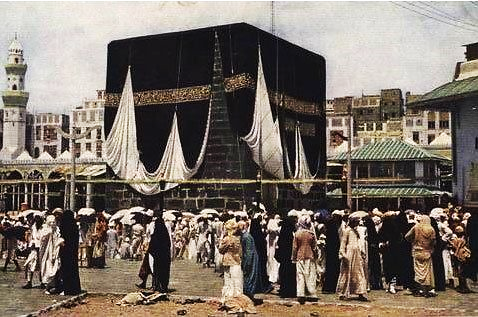

However, the holy city of Makkah, with its holy mosque (al-masjid al-haram) and as the site of the hajj and umrah pilgrimages, was an exception. It was the spiritual and physical focus of all Muslims. All paths were leading to it, and all yearnings, aspirations and hopes were directed towards it. It was the source of inspiration, guidance and optimism, and, at the same time, the end of all not merely otherworldly (spiritual), but as well worldly (material) ends.

To Muslims, therefore, Makkah was a sanctuary and haven, and to non-Muslims an unapproachable mystery and colossal dilemma. To Muslims, furthermore, it was a utopia “ at least in the conceptual and spiritual senses. Its definitive purity and sacredness, as far as Muslims were concerned, meant prohibition and inaccessibility for non-Muslims. As a free and safe city by a heavenly decree, Makkah was always an icon, a promoter and facilitator of freedom. Historically it was designated as al-mukarramah, which means œvenerated and œhonoured.

All these connotations and roles of Makkah were significantly augmented in particular at the outset of the 20th century when the Muslim world with its culture and civilisation was on the brink of total disintegration and collapse. As Muslims were losing their directions, Makkah was (re)establishing itself all the time more as the direction; as they were bracing themselves for gloomier-than-ever days ahead, the light of Makkah was proving inextinguishable and also as the only potential hope on the horizon; and as they were experiencing dystopias and nightmares virtually everywhere else, Makkah was proving a celestial city and a firmament, blind to colour, race, geography and nationality – and was beckoning as such.

In short, Makkah was a bolthole and a safe haven par excellence. It was a global and cosmopolitan urban phenomenon. It was a microcosm of the world, yet of all existence. It was a living miracle. In point of fact, Makkah was only that which it was meant to be from time immemorial. According to the Quranic message, Makkah was to be a place of visitation or return for people (al-Baqarah, 125); the mother of all cities and villages (qura as both urban and rural environments) and all those around it (al-Anam, 92); the city of safety and security (al-Balad, 3); the city to which mankind will come on foot and on every lean camel (using all modes of transportation) and from every remote path and distant quarter (from all parts of the world) for the annual hajj pilgrimage (al-Hajj, 27); and to be a safe sanctuary immune from violence, while mankind will be recurrently ravaged all around it (al-˜Ankabut, 67).

The following verse of the Quran to some extent exemplifies the status of Makkah: œAnd they say: ˜If we were to follow the guidance with you, we would be swept from our land. Have we not established for them a safe sanctuary (the city of Makkah with its holy mosque) to which are brought the fruits of all things as provision from Us? But most of them do not know (al-Qasas, 57). The words œthe fruits, or produce, of all things (thamarat kulli shayin) could also imply all sorts of material and immaterial yields and benefits of the world which will be drawn – somehow or other and in different capacities – to the city of Makkah and its people.

Undoubtedly, as such Makkah was a cause for concern to the Western imperialistic culture. Colonisation masters across Europe perceived it as a stumbling block and an insurmountable conundrum. It was a thorn in their sides. They were right, though, as, in the end, Makkah emerged as a safe haven for anticolonial sentiments and programs. Similarly, it proved a main catalyst for the notion and movement of pan-Islamism (Muslim universalism or modern caliphate) as a political ideology that promoted the idea of Muslim unity under a single Islamic state or a transnational organisation. The annual hajj event was a global Muslim conference on unity and Muslim struggles. People exchanged ideas (both in oral and written forms), evaluated strategies and challenges, and – if nothing else – surrounded by Muslim brethren, they rehabilitated their faith, optimism and courage.

Basil Mathews was fully aware of this status and function of the holy city of Makkah. He proclaims that Muslims en bloc, and young Islam in particular, were moving out on a trek, but whither (that is, to what place, destination and direction), to what purpose, and under what leadership and whose guidance. His Chapter One titled œIslam strikes its tents inside his book œYoung Islam on Trek: a Study in the Clash of Civilisations he concluded by emphatically asking those questions and eloquently articulating his scepticism. However, in subsequent Chapter Two titled œCaravans to Makkah the author in the first place speaks about multitudes of Muslims from many parts of the world and how they by means of camel caravans, railways, village tracks, dhows (sailing ships) and steamboats, had arrived for the hajj. Subconsciously rather than consciously, Basil Mathews recognised thereby the quintessence of the answers to the most vital aspects of his queries. As if he unintentionally alluded that the supremacy of Makkah, and everything it embodied, might hold some answers.

The numbers and facts associated with the hajj were staggering. The scene of the streams of pilgrims travelling form Jeddah as the gateway to Makkah as the final destination was astonishing and the messages thus radiated extraordinarily profound. In Basil Mathews mind, so tremendous was the multitude of pilgrims that the string of camels often seemed continuous all the way from Jeddah to Makkah. Thousands of other pilgrims went on foot, walking single file, along the path winding among the hills. Before the First World War œhalf a million people would travel this route in the month of pilgrimage. For some years between 1914 and 1924 the numbers were greatly reduced, first by the war, then by the conflicts of the Arabs.

Basil Mathews tried to expound how “ before venturing into answering why – Makkah is special and its unusual lure irresistible. He for instance said that no sooner do pilgrims pass two white stone pillars that mark the entrance to the holy ground or precinct of Makkah, than everybody stops talking, for the awe of the city and its holiness descend on them. It is as though they were suddenly transported into a different metaphysical realm. Prayers alone break that silence. œThe camels pad forward over the sand without sound. In a few hours the pilgrims feet will walk within the city toward which they have bowed their heads five times a day since boyhood. The awe-inspiring sanctity, as of the very presence of the Most High – that for the Hebrews hung over the Tabernacle – breathes from Mecca for the devout Moslem. Moving forward the pilgrims repeat a special prayer in a wailing chorus. When pilgrims finally arrive at the gates of the holy mosque (al-masjid al-haram) “ œthe sacred enclosure that holds the centre of their world: the Kabah “ they enter in awed silence. The sight of the interior overwhelms even the most careless.

With the completion of hajj rituals a person becomes a œholy man. He becomes an exemplary Muslim and so, an asset to Islam. He becomes a member of the great brotherhood of pilgrims which denotes the nucleus of Muslim universal brotherhood whose soul, in turn, is a brotherhood of common devotion everlastingly fostered during the hajj. And that was the true meaning of the pan-Islamic brotherhood of the early 20th century which all enlightened and progressive Muslims craved for, and which the forces and protagonists of Western colonisation feared most. That brotherhood represented the pinnacle of the Islamic faith. It was Islam-in-action, so to speak.

By way of example, it was impossible for a regenerated and awakened pilgrim “ a œholy man as styled by Basil Mathews “ firstly not to feel a pang of guilt at supporting and being loyal to an infidel government in his country and to do nothing about getting rid of it, and secondly not to feel sympathetic towards his fellow Muslim brothers across the world, who were experiencing the same fate, and not to try to help them in whatever ways he could. That surely would have amounted to a betrayal of his Islamic consciousness, Islamic duties and, of course, his newly-acquired Islamic rank.

While on hajj, every pilgrim witnessed and experienced the most beautiful and most profound dimensions of Islam, which however were inhibited back home, partly or completely, by the authoritative administrative presence of the infidels and their domestic collaborators. Hence, if the hajj served as an eye-opener and a manner of reality check, its aftermath signified a process of perpetual yearning for the actualisation of Islams impeccability and grandeur. As Basil Mathews deduced at one point that enormous consequences with regard to colonisation agendas have originated from the effects of the hajj, and many more were yet to come.

This is how Basil Mathews explained the background of the pan-Islamism and anticolonialism currents in Makkah. Those pilgrims œare from many lands. Brown-faced, black-haired Moros from the Philippine Islands mingle with a group of Arabs, lean, swarthy, black haired, keen eyed, their muscles of whipcord rippling under the glossiest of all human skins. A tall pale faced handsome Circassian like a Greek god moves swiftly round the Kaaba. Dark Egyptians, and behind them the hook-nosed, fierce-eyed visage of a mountain Afghan, are flanked oddly by the smooth corpulence of a wealthy Syrian merchant from Beirut and the broad heavy strength of a negro from Cuba. A Turkish high official from Konia, in the heart of Asia Minor, finds near him a hawk-eyed, cruel-jawed Kurd from the mountains above Mesopotamia; while in front of them are a mild-faced scholar from his study in the rose gardens of Tehran on the high plateau of Persia and a Baghdad merchant who has made a fortune in Mesopotamia out of petrol. The skin of a Chinese Moslem glints strangely in the sunshine beside the jet black and chocolate brown of a group of negroes from Abyssinia, the Sudan and Nigeria; and behind them run two Javanese from the Dutch East Indies and a ˜flying column of Indians from Delhi. Lithe, dark youths from Algiers in a group together with fellows who have come with them from Tunisia and Morocco, give a picture of North Africa in sharp contrast with the bearded light-skinned south Russian Moslem. Rich and poor, rulers and subjects, scholars and ignorant, men speaking scores of languages and of fifty nationalities, stripped of every trapping of wealth or knowledge or power, run bare-headed under the blazing sun and barefoot on the grinding gravel in a brotherhood of common devotion round that central pivot of Moslem loyalty, the Kaaba and the Black Stone. They have been drawn from their businesses and their homes, from government offices and universities, from the counting-house, the bazaar and the camel caravan, from the vineyard and the workshop. They have been drawn across thousands of miles of land and sea, by blistering desert track and by ship, by railway train and motor car, on camel, horse and ass, and on foot, to this sun-smitten arid city in the heart of a land of red sand and rock.

The hajj with all its ceremonies symbolised “ and highlighted – the dormant potentials connected with Muslims as one nation (ummah). Referring to some of those potentials which were called to mind during the course of the tawaf (circumambulation around the Kabah), as for instance, Basil Mathews employed such expressions as œthousands surging in one direction, œthe tornado of movement, œthousands roaring like breakers on a shingle shore and œthousands seeming like an indescribable human whirlpool. Parenthetically, the author for illustrative purposes dwelled only on the ˜umrah as the lesser pilgrimage. He did so, most probably, because the ˜umrah is the small-scale version of the entire hajj episode and practically its prelude; or because he did not know exactly the subject matter, was never in Makkah and so, was jumbling.

Without a doubt, the hajj was the most powerful embodiment of the universal principles of unity in diversity, unity of purpose, shared vision, ultimate truth, equality and solidarity. Those were mighty assets against which no ideology or paradigm could make a stand. Muslims possessed those assets, at least at the conceptual plane. Unfortunately, every so often they underutilised, mismanaged and even abused – in varying degrees – those assets, without knowing that their strength and success depended exclusively on them. The extent of the former was always proportionate to Muslims faith in and commitment to the latter. Indeed, all other assets “ that is, potencies and gains “ were predicated on those mentioned qualities.

The adversaries of Islam and Muslims were all too familiar with that, hence their fascination and preoccupation specifically with Makkah and its hajj sacrament. Basil Mathews was no exception. He spoke a lot about the values and meanings of the hajj pilgrimage, which together were so great that they made it the sole real symbol of unity in the entire Muslim world.

From his perspective, the hajj had two main values. œThe first and original value of the pilgrimage is its effect on the pilgrim in stirring an intense emotion of crowd-psychology. The pilgrim glows with pride in his membership of this mighty inter-racial brotherhood. The second value of the pilgrimage is the indescribable radio-activity of this emotion all over the Moslem world. The caravan trail runs back from Mecca into a score of lands; and along that trail the pilgrim carries a penetrating influence.

The pilgrim was furthermore a source of motivation to others. When he returns to his homeland he commands and exudes an awe-inspiring aura of prestige. He shares his new experiences and wisdom about what he had seen, heard and felt. He talks about other Muslims and their countries, and about what he had witnessed and learned concerning their successes and hardships. He thus also becomes a source of information. He becomes an influencer and an authority. The pilgrim in addition may paint in colours upon the wall of his house some scenes of the pilgrimage trip – such as the camel caravan, the railway train, the ship, the holy mosque in Makkah and its Kabah, a Makkah landscape with some of its holy sites, etc. – so that the revolutionary life chapter and emotions associated with it were immortalised and their effects in perpetuity communicated to others. To the pilgrim, therefore, the hajj as a rite denoted a personification of the whole of Islam; as a spectacle it denoted a personification of the whole world of Islam; and as an experience, it denoted a sign of a rebirth and a new beginning.

As an antagonistic non-Muslim and missionary, Basil Mathews believed that the hajj has normally nothing to do with holiness in any spiritual or moral sense. However, he could not deny that the psychological effect of the hajj was irresistible. But the paradox “ not to mention the problem – was that the weaker and less spiritual Muslims were the greater influence the hajj had upon them. As Basil Mathews puts it: œAnd the lower the standard of intelligence or civilisation the more overwhelming is the effect. Elaborating his point, the author said: œHardened Turkomans of the Central Asian plateaux will weep with excitement at the sight of one of their own folk coming back from the Mecca pilgrimage. Afghan brigands on the one hand, and Negroes in the Sudan or Nigeria on the other, are overwhelmed with awe. So also are the relatively more advanced Moslems of Delhi or Cairo. They will kiss the pilgrims footsteps, rub his dress on their cheeks to get an atom of the dust of the Kaaba, and embrace him.

While on the hajj, many pilgrims ended up asking, as a result of new wisdoms and encounters, why most Muslims were ruled by infidels and why to endure, let alone accept, such an abnormality. The norm that Muslims were supposed to rule not only Muslims, but also non-Muslims, so as to let them live through the beauty and integrity of Islam, was repeatedly exclaimed as well. That Muslims were ruled by non-Muslims was seen “ and insistently marketed – as utterly sacrilegious.

Accordingly, those pilgrims developed in themselves a vehement conflict of loyalties. They became unsure whether they should be (remain) loyal to infidel colonial governments at home, or should pursue the pan-Islamic brotherhood agenda which they had seen and were stirred by while in Makkah. That conflict of loyalties during the early 20th century pilgrims carried back with them to the Dutch East Indies, to India, Syria, Palestine, or North Africa. Many troubles for colonisers and their missionaries resulted therefrom and many more were looming – was Basil Mathews conclusion. It was only from Makkah, as the burning pan-Islamic and anticolonial centre, that the power of Islam radiated into every continent.

The secret of the hajj in loyalty to a man and a message

Having explained how compelling, challenging and even dangerous the hajj and its locus: the holy city of Makkah, had been for the imperialism-obsessed West within the framework of the vicissitudes of the early 20th century, Basil Mathews proceeded to elucidate why such was the case. He did that in order to try to penetrate the deepest doctrinal recesses and imports of the hajj and to thus enable himself “ and others “ to assail them and undermine their at once theological and rational legitimacy.

He knew all too well that by adulterating and enervating the hajj phenomenon, he was doing the same to the total edifice of Islam and its civilisational prospects. He moreover was aware that along the similar lines he was providing excellent services to the westernisation and colonisation efforts, as a result of which Christian missionaries were also finding themselves on the receiving end of all the benefits featured in the endeavour. The author was convinced that in such a manner he was doing his bit to swing the balance of the ongoing clash of civilisations in favour of Western civilisation.

Basil Mathews therefore unambiguously asked, hinting thereby at the second dimension of his investigation: œWhy? What is this Faith that holds their (pilgrims) passionate loyalty? What is the bond of this brotherhood? What unites men of all these races and classes into a freemasonry so submissive to the authority within, so arrogant to all authority without?

His answer was twofold: a man (Prophet Muhammad) and a message (the religion of Islam). Islam as a historical religious, cultural and civilisational force enjoyed a commanding appeal to its immense range of followers because of the appeal of loyalty to a man, to a message, and to a brotherhood, with the last component arising and deriving its validity and vigour from the first two.

Basil Mathews then wondered if that appeal of Islams triad was built on enduring foundations, or if it was ever more slowly but surely undermined. His resolution, obviously, was in consonance with the latter scenario, after which he decided to substantiate the matter by making an effort to discredit both the status and character of Prophet Muhammad (the man) and the religion of Islam (the message).

Attacking Prophet Muhammad

The first thing that Basil Mathews embarked on was the dishonouring and bringing into disrepute the personality and mission of Prophet Muhammad. In doing so, he thought was able to sow a seed of doubt in the minds and hearts of Muslims concerning the fundamentals of Islam, and to strike at the foundations of everything Islamic, including the status and role of the holy city of Makkah and the influences of its hajj.

Needless to say, however, that Basil Mathews did nothing special, nor utterly new. In a condensed mode he only brought forward the majority of misconceptions and errors about Islam and its Prophet which teams of Christian polemicists and missionaries had been concocting and articulating for ages. He similarly propounded the majority of grave and irrational allegations that had become the favourite themes “ in actual fact, mere clichés – of all the advocates of colonisation and islamophobia. He thus only tried to frame and implant those into his admittedly unique discourses about Makkah, hajj and the clash of Islamic and Western civilisations, adding to the growing piles of the Orientalist and missionary intellectual litter.

To begin with, the author portrayed the young Muhammad in Makkah as being exposed to no elements of refined culture and sophisticated civilisation. Most of what he could hear and be familiar with “ and learn from as well as adopt – was the life and practice of highway robbery and plunder. œHe tumbled about in the desert sand, drank camels milk, wore a cloak and girdle of camel-hair, and slept under a camel-cloth tent. Camel-tracks in the sand were his only alphabet, and the tales of raiding and brigandage (highway robbery and plunder), of merchants and the fights of Arab tribes told round the caravan fires at night his only history and adventure books.

Additionally, Muhammad was depicted as an impostor and charlatan. He was a false prophet. The monotheistic idea of Islam suddenly œburned in his mind. He interpreted his hallucinations and visions, which often came to him in his dreams and in states of ecstatic vision, as a heavenly call to be a missionary of the divine unity, that there was no god except Almighty God, Allah. The simplicity of this creed he then completed with a clause that œMuhammad was the Apostle of God.

Muhammad was also alleged to be a crafty manipulator. The Quran was his own production and was a marvellous blending of spiritual vision and cunning, lofty and low morals, mercy and intolerance, moral reflections and historical summaries of Biblical prophets and kings.

He moreover was a violent man. He was a coward too. In Madinah, he created and commanded a vigorous, united and passionate fighting force. œHe harried the wealthy caravans of Mecca. By his flaming spirit he drove men on to fight and inspired victory, though he never hazarded his own life in conflict. He gave, however, the essentials of military success – discipline, enthusiasm, and military skill.

The system that he fashioned was in essence military. As a result, Islam always spread by the sword as the main method. œOther methods, like the purchase or forcible seizure of Christian children, sometimes in vast numbers, and the missionary influence of travelling traders, helped.

The excessive violent and militaristic penchant of Islam and Muslims Basil Mathews explained like this. œThe Moslem creed is a war-cry. The reward of a Paradise of maidens for those who die in battle, and loot for those who live, and the joy of battle and domination, thrill the tribal Arab. The discipline of prayer five times a day is a drill. The muezzin cry from the minaret is a bugle call. The equality of the brotherhood gives the equality and esprit de corps of the rank and file of the army. The Koran is the Army Orders. It is all clear, decisive, ordained – men are fused and welded into a single sword of conquest.

Nevertheless, with military and political success, inevitably, came moral decadence. Muhammad became a personification “ and synthesis “ of aggression, immorality and deceit. He was the one who started in Islamic civilisation the culture of harem (understood in this particular sense as a pleasure place reserved for ones many wives, concubines and female servants). He married numerous wives, massacred old men and children, and on one occasion even slew a man and in a few days added the dead mans wife to his harem. Worse still, justifying his ill deeds, he pretended to have been inspired and directed by God to do whatever he had been doing.

Basil Mathews concluded his barrage of standardised accusations and lies by positing that morally – after the death of his first wife, Khadijah – Muhammad was œwhat most seventh century Arabs would have been in his place and power. By this means, though, having œrationalised and œjustified the wickedness of a time and place, the author shrewdly opened the door to the potential œrationalisation and œjustification of all the subsequent chapters of Muslim civilisational iniquity and sin. It all revolved around an interplay of spiritual pretence, moral profligacy, intellectual stupor, and undying passion for savagery and violence, with diverse time and space contexts contributing their own flavours to the persistent ethos.

Attacking the Prophets message and legacy

The second thing that Basil Mathews has done, with the aim of undermining the reputation of Makkah as the birthplace and midpoint of Islam, including the impacts of its hajj, was an attempt to defile the message brought by Prophet Muhammad. The objectives of the exercise was similar to the ones behind his attacks on the personality and integrity of the Prophet; that is, to throw discredit and suspicion upon the underlying principles of Islam as a religion and a civilisational force, and to sabotage, as well as incapacitate, every sort of cultural and civilisational legacy that had originated therefore.

If the message and mission of the Prophet were dented successfully, every other undertaking and mission correlated with it, regardless of time and place, would inevitably be dented too. In which case it would also be easy to knock down the prospects of reviving those expired thoughts and their operational templates, and to consider them as a viable option in the modern, innovative and forward-looking world. In that event, Makkah and hajj, too, would correspondingly start losing their appeal and would have to take on an altered ontological worth and an adapted civilisational veneer if they wanted to survive the onslaught and to stay relevant.

The circumstance would become such that Muslims will have no choice but to look elsewhere for œcentres, œdirections and œinspirations. They will have to search for another paradigms and œqiblahs. And that is exactly where the Christian West and its ostensibly superior culture and civilisation were expected to come in. Everything that Muslims were lacking and were in desperate need of – such as thought, morals, weaponry, science, technology and all the socio-politico-economic institutions and standards of living – was to be promoted and served to them. It was anticipated that in so doing, the West will eventually be seen as an ally and even a saviour. The enterprises of colonisation and westernisation, coupled with delicate evangelisation, were likewise to be seen as the means of the liberation and rescue processes.

The first idea that Basil Mathews came up with was the standard accusation that Islam was a plagiarised religion. For its substance and much of its contents, Muhammad copied and distorted significant portions of the teachings of Judaism and Christianity and of their holy books.

Basil Mathews firstly said that as a twelve year old boy, Muhammad was taken by his uncle, Abu Talib, who had earlier adopted him, a thousand miles by camel caravan to Syria with merchandise. There they saw Christians and Christian churches, but heard no Christian teaching. Basil Mathews then lamented: œThe history of the world might have been different if anyone in Syria had taught this Arab youth the truth about Christianity.

Moreover, implying that Muhammad was a heretic and his teachings a mere heretical either Jewish or Christian sect – just like many other heretics and heretical sects that had appeared, and disappeared, on the vast Judeo-Christian scene “ Basil Mathews said that the Prophets first wife, Khadijah, belonged to a sect of Arabs who had learned from the Jews the idea of one God. œTo this thought Mohammed soon became an enthusiastic disciple.

Muhammad in those years had also some contacts with Christians in Arabia. Even his adopted son, Zayd, was from a Christian tribe of Arabs. However, the teachings of the Church there had become so debased and its life so stagnant that Muhammads ideas concerning Christianity were garbled and confused, and in essence wrong. It follows that even if he genuinely wanted, Muhammad could not learn the truth about Christianity, which doomed him to a life of confusion and error. In the same vein, Basil Mathews claimed that the Quran contains sheer summaries of the accounts of numerous biblical prophets and kings. As such, it is an evidence of replication and fraud.

In passing, the first person who mooted the idea that Islam was a plagiarised religion was John of Damascus in the eighth century. He identified Islam with Arianism, which denied the divinity of Christ. He devised a theory to the effect that Muhammad did not formulate his Islamic heresy until after he had come across the Old and New Testaments and after he had met and conversed with an Arian monk in Syria. The monk taught Muhammad about the created-ness and non-divinity of Jesus, the view which they both shared. By the time Martin Luther had to battle in the 16th century the bane of Islam and its agent in the form of the Ottoman Turks, the theory that Islam was a fake and plagiarised religion was fully developed and its articulation at maximum capacity. Thus, in his influential book œOn the War against the Turk Martin Luther called attention to the true nature of Islam. To him, it was a plagiarised religion patched together out of œthe faith of Jews, Christians and heathen (pagans and idolaters). Hence, Prophet Muhammad was regularly compared by Christian apologists and polemicists to the famous heretics of the Christian heritage, and his views to theirs. Examples of those heretics are: Arius (d. 336), Eunomius (d. 393), Carpocrates (d. 138), Cerdonius (2nd century), Manichaeists (3rd century), Donatists (4th century), Macedonius (d. after 360), Cerinthus (d. 100) and Nicolaitans (some of earliest heretics).

Basil Mathews alleged next that Muhammad did not receive any revelation from God. What he claimed to be the revealed message (book) was a combination of his hallucinations, dreams and ecstatic visions. A revelation process was styled as a bright light coming to him as a vision with a voice. These were then interpreted and applied unilaterally and as Muhammad pleased. The thoughts and messages thus generated and received were regarded “ and advertised – as the direct word of God uncoloured by the human medium. Their absolute inerrancy has been of the very essence of Islam ever since.

In addition, the word œIslam means œto submit and its participle œMuslim means œsubmitting and one who submits. Therefore, the concept of submission – to a man and an idea “ became to Muhammad the watchword of the new religion, œjust as, for instance ˜Repent had been the word to that other desert prophet six centuries earlier, when the stormy voice of John the Baptist rang across the waters of the Jordan a thousand miles to the north of Mecca. Some of the implications of the concept of œsubmission were the spread of Islam by force, insatiable conquest and forced conversion. Islam was a flaming fighting faith. At the point of the sword it called people to its fold, and to submission and obedience. Those who refused to submit were put to the sword.

Basil Mathews elaborated: œSo to be a Moslem – or a Mohammedan – was and is to believe that God is One and that this Arab Mohammed of Mecca is the voice through which the will of God has been revealed to the human race. Mohammed, from the early days, held that all who embraced Islam were equal members of a brotherhood, irrespective of any privilege of family, race or wealth, and that that brotherhood was a warrior-state which absorbed and dissolved within itself all whom it conquered. It was a nation destined by the will of Allah to be the dominant and inclusive nation.

In consequence of these tactics, during the first centuries of Islam “ Basil Mathews wrote, relying on Gibbons estimations – œIslam overwhelmed thirty-six thousand cities, towns and castles, destroyed four thousand Christian churches and erected in their places fourteen hundred mosques. In later centuries the Moslems poured across the Taurus Mountains, overwhelmed Constantinople, and hammered at the gates of Vienna; flung their forces eastward, harried Central Asia and came to the Great Wall of China; foamed down the passes into India and set up a mighty throne in Delhi. What happened in the wake of these conquests? The surviving population became Moslem for the most part. The Koran became the law, criminal and civil, controlling taxation, trade, government, everything. Mosques were built. In Jerusalem, for instance, where Abraham sacrificed and Solomon built his temple, Omar (the second caliph) built the Mosque of Omar. Governors and magistrates enforced Moslem law. Teachers made the new generation learn the Koran and the ritual of the faith. The Moslem caliphs of Baghdad reigned over one of the greatest empires the world has ever seen. Their wealth was indescribable and their state outdid the wildest romance in its profusion of gold and precious stones, palaces and tapestries and pomp and circumstance. Learning flourished. All the known wisdom of the world was translated into Arabic. It was from Arabic (translated into Latin) that practically all scientific and philosophical knowledge – for example, Aristotle – reached Europe in the Middle Ages.

Basil Mathews at that point gladly observed that the thought in question “ together with the rest of achievements of Islamic civilisation “ œwas not that of Arabs; for the greatest Moslem authors have been Persian; the finest generals and soldiers have been Turkish; Moslem mysticism has been largely fed from India and Persia, Spain and Africa; while much physical beauty has come into the Moslem world through the Circassian, the Greek and the Armenian.

However, Islams faulty foundations and Islamic civilisations faulty frame of reference were not to last forever. Having reached their climax and having had the world at their feet, they started withering; their long term reliability was increasingly doubted. The dark sides of Islam and Muslims, and their yet darker aftereffects, were becoming self-evident and were completely taking over. What was initially held as qualities and strengths gradually degenerated into deficiencies and spectacular failings.

Basil Mathews explained: œThen decadence set in. The early caliphs in Baghdad reigned resplendent. But the move from the Spartan rigours of Medina in the desert to the luxurious, languorous heats of Baghdad on the Euphrates, was the symbol of a moral corruption. The caliphs court became a purulent sore, simultaneously sucking the strength from the body and poisoning it. Baghdad bled the empire white with its demand for slaves and riches. Caliph rose against rival caliph. Internecine war began. The jihad (holy war) was degraded to an organised system of massacre and loot. The fine elements of culture and art, and the wonderful beginnings of science that radiated over the world, were stamped out when the Turcoman hordes of barbarians in the twelfth and thirteenth centuries swept down from Central Asia, captured the Islamic control and created Turkey. By rottenness within, and through the increasing strength of the European races without, Islam was gradually dismembered.

As far as Makkah was concerned, Muhammad did not destroy the Kabah “ to the peoples amazement and by a stroke of genius, on the word of Basil Mathews – but made it and the whole city the centre of his own religion. He made the hajj pilgrimage a fundamental of Islam. He had a reason for that, which was not only religious, but also economic and patriotic.

Basil Mathews further held that historically Makkah had nothing to do with the revealed monotheistic faith. It was a place steeped in ancient pagan or animistic beliefs and rituals. It also featured a pilgrimage ceremony down the same religious path, which had been evolved by the wandering Bedouin tribes. Due to that, œin some century far back beyond the edge of written history Makkah was already developed, to a certain extent, as a regional religious centre.

Makkah is a barren sun-smitten desert spot, hostile to human settlement. Its topography repels, rather than attracts life in general and human existence and activity in particular. There is virtually nothing there that could engender elements of civilisation. In its origin, the city was a tiny camel oasis cantered on the Zamzam well. œHidden in its hot, barren, narrow valley, broiled in the heat from the brazen sky between the high stony surrounding hills, Mecca would dwindle to a caravan market were it not for the pilgrimage. In other words, without pilgrimage Makkah would have been inconsequential and would have played a negligible role even in a small local context. Practically, it would have been wiped off the map.

Muhammad was aware of all that, Basil Mathews claimed. Hence, in order to œsave and œupgrade his native city, Muhammad retained the pilgrimage culture, adjusting it to the requirements of his own new monotheistic religion. Then, with the growth of Islam as the new religion, Makkah grew and prospered as well. The success of Islam was its own success. Consequently, it grew into a metropolis. It became the most important and most talked-about city in the world. It became an international centrepiece. To Muslims, it is the spiritual orientation, and to the rest, the object of perpetual curiosity and a mystery œmore jealously guarded than the Holy Grail. So much so that in English there is a word œmecca which means œany place that is regarded as the centre of an activity or interest and œany goal to which adherents of a religious faith or practice fervently aspire. Hence, while the Muslim world at large was crumbling at the dawn of the 20th century and was standing at the most critical juncture, Makkah continued functioning as the epicentre of pan-Islamism and anticolonialism. It in addition was a conduit for ideas to exacerbate what Basil Mathews termed as the clash of civilisations.

However, Basil Mathews contended that just like the whole edifice of Islamic civilisation, Makkah, too, eventually had to decline, exposing the true colours of the religion it exemplified. If it did not plunge into the abyss of history and civilisation, it ultimately did plunge into a spiritual and moral abyss. It became the embodiment of all the negativities associated with Muhammad and his invented religious teachings.

According to Basil Mathews, flagrantly exceeding all limits of honest critique, plus scholarship: œAs a result the Meccan attitude to the pilgrimage is largely commercial. The people there fleece the pilgrims unmercifully. A slave market exists in which the commodity for sale is largely young women. The city is saturated with immorality. Two quarters of the city are occupied by professional prostitutes for the pilgrims. Many good Moslems are as scandalised by Mecca as Luther was by the abuses of a very different kind of the pilgrimages to Rome.

Basil Mathews final missionary advice for Muslims and their youth

Basil Mathews thus wanted pilgrims “ and Muslims in general with their youth blazing the trail – to see the full picture of Islam and its civilisational trajectory. He wanted them to see the other side of the coin as well, and to assess the situation as objectively as possible. Makkah and its hajj, for starters, could be used as a case study. So, before the eyes of pilgrims, performing rites or sitting in the colonnades of the holy mosque in the vicinity of the Kabah, there should unroll, as on a moving picture reel of history, the spectacular not just rise, but also the fall of Islamic civilisation. The present time ought to be interpreted as a net product of the past times.

Since the turn of the 20th century Makkah exemplified the decadence of Islam. It did so, chiefly, through the confused mental states of its pilgrims. It also presaged a bleak future for Islam, in that most of the countries represented by pilgrims were controlled by mighty Western powers which certainly meant business. Makkah, it stands to reason, was an epitome of Islams new destiny, and was a reminder. As such, it was turning by the day into a home of paradoxes. It was a centre of fragmenting and increasingly isolated peripheries. It was becoming the direction of the misdirected, and the orientation of the disoriented.

Finally, Basil Mathews wanted pilgrims “ all Muslims “ to use the conditions of Islam and the Muslim world as a background against which the Western presence in their national midst could be fairly assessed. If the fall of Islam and its civilisation was the result of the working of the forces (laws) of history and of the rise and fall of civilisations, so was the rise of the West and its civilisation the result of the same forces. If the fall of Islam was a destiny, the rise of the West was a destiny too. And lastly, if Islamic civilisation was a chapter in the story of humankind, and a phase in its enlightenment evolution, Western civilisation in the end triumphed over and surpassed it, and in its stead, took up the reins of global leadership. The two civilisations, ever since they clashed, kept moving in opposite directions.

Owing to all these realities on the ground, Muslim youth especially “ as part of the worlds youth full of superficial contrasts and profound similarities – were advised by Basil Mathews to view the presence of œinfidel Westerners as their overseers in a different light. They should be more accommodative of the Western paradigm and of their life systems while on a new trek, while searching for a new purpose, a new direction, and a new guidance. The West, after all, might not be as bad as originally projected. It might yet hold the needed answers, especially if it became aroused and aligned with the authentic spirit and teachings of Christ.

Muslim youth had a range of options within the suggested framework. They all revolved around four thrusts: personal and national scepticism, modernisation-cum-westernisation moderately rooted in selected traditions, nationalism, and what Basil Mathews dubbed œa national conversion which is the total œabandonment of one way of life or civilisation and the adoption of another.

The author explained the predicament of Muslim youth as follows: œIt is certain that young Islam has struck its tents and is on the march. No one, however, can yet answer the questions ˜Whither? ˜Under what banner? ˜To what goal? The air is full of rival cries. Some say ˜Forward, others cry ˜Backward. Some declare for race war; others plead for racial co-operation and world peace. Some work for a League of Moslem Nations to face in hostile array a League of European Nations. Others work for a world fellowship of nations. Some, again, believe in a reformed and liberalised Islam; others fight for the ancient ways and the primitive gospel of Mohammed; still more declare for a frankly materialistic, scientific agnosticism. There is no master word; there is not even a ˜master sword as there was in the beginning of Islam. There is today no accepted, supreme Prophet, who can sound a universal call to the world of Islam. What, then, is to happen? What can be done? Let us examine the possibilities. First, can we have a liberalised Islam? Can science and the Koran agree? Conviction grows that the reconciliation is not possible. Islam really liberalised is simply a non-Christian Deism. It ceases to be essential Islam. It may believe in God; but He is not the Allah of the Koran, and Mohammed is not His Prophet; for it cancels the iron system that Mohammed created.

Only ecumenism and Christ could œsave Muslims

In the opinion of Basil Mathews, neither Islam, nor Western civilisation, nor Christianity could truly save Muslims and their restless youth. Islam was unable because Muhammad and the faith that he gave to the world can never give millions of Muslim youth a master word for living their personal lives and for building a new order of life for their lands. Islam is not in a position to lead them to the desired goals. œFor, with all the truth that Islam indeed contains, it is eternally cramped within the walls of its origins and tied to the fatal flaws of its founder. It can have no place as the basis for a world-order or for individuals in that order.

Western civilisation could not do that either, because œobsessed by material wealth, obese with an industrial plethora, drunken with the miracles of its scientific advance, blind to the riches of the world of the spirit and deafened to the inner voice by the outer clamour, Western civilisation may destroy the old in Islam, but it cannot fulfil the new.

Nor could the Churches of Christendom, separately and as they existed at that point, rise to the occasion and œrescue Muslims. œLimited in their vision, separatist in spirit, tied to ecclesiastical systems, the Churches of themselves if transported en bloc to the Moslem world, would not save it. They have not saved their own civilisation (so how could they save the one of Islam?).