By Spahic Omer

Joseph Pitts (1663-1735), an Englishman, was the fourth known European non-Muslim to visit Makkah and Madinah. He was preceded by Ludovico di Varthema (d. 1517) who secretly visited the holy cities in 1503, Vincent le Blanc (d. 1640) whose alleged and also clandestine visit took place in 1568 (which however is dismissed by many as fictitious), and Johann Wild (d. ?) who was there as a slave in 1607.

Just like Le Blanc, Pitts from his young age was fascinated by the prospects of travel and exploration. He was a genius, according to Richard Francis Burton (d. 1890). He was determined to make the most of the Ages of Exploration and Discovery that were taking Europe “ and increasingly the rest of the world “ by storm. The entire world was becoming ever more discovered, accessible and known. Enthusiasm and elation knew no bounds, nor did opportunities and expectations.

Almost on a daily basis new heroes were born, new breakthroughs made, and new outstanding chapters of human history permanently inscribed. With the planet earth being all the time more explored and understood, the sky “ literally “ was becoming the limit.

However, there was a dark side to the mania. There were myriads of uncertainties and outright dangers lurking in the dark. Many people in many places did not share the outlook. To them, the novel developments meant something else, and contained a whole new world of different opportunities “ as Pitts soon discovered and learned the hard way.

Pitts story is one that highlights how fine the line was between opportunities and dangers, exhilaration and adversity, and between hopes and despondency. Seldom did things go according to a plan.

Who was Joseph Pitts?

Pitts was born in Exeter in 1663. Owing to his immense love of travel and adventure, he became a sailor at the age of fifteen. He wanted to see the world. After some short voyages, he accomplished one to Newfoundland (a large island off the east coast of the North American mainland), œbut on his return his ship was captured by an Algerine (Algerian) pirate off the coast of Spain. The pirate captain was a Dutch renegade (a Christian who accepted Islam) who spoke English, but to Pitts the enemy appeared like ˜monstrous ravenous creatures, and he feared they would kill and eat him. Three more English ships were taken.

Once in Algeria, at Algiers (the countrys main port and the chief seat of the Barbary pirates and privateers who through the 16th and 17th centuries captured thousands of predominantly European merchant ships and enslaved tens of thousands of people), Pitts was sold into slavery. He had three masters. The first one was reasonable and did not attempt to convert him to Islam. But the second one was the polar opposite.

The second master was the œcaptain of a troop of horse, was a profligate and debauched man in his time, and a murderer, who determined to proselyte a Christian slave as an atonement for past impieties. Pitts was his chance. He began by large offers and failed, after which various forms of torture followed. When the cruelty became most intense and pain unbearable, Pitts felt compelled to ostensibly accept Islam and to pronounce the words (testimony, shahadah) to the effect that there was no god but Allah and that Muhammad was His messenger. He had to do this by œholding up the forefinger of the right hand. He was then circumcised. However, even after conversion, Pitts was regularly abused and maliciously beaten.

Surely, that conversion was not a sincere one and Pitts tried his best whenever he could to demonstrate that, either by words or deeds. Through his infrequent and secret correspondence with his family, his father kept encouraging him œno matter what cruelties were practised upon him, never to renounce his blessed Saviour. After he informed his father about what had actually happened, the latter responded, as solace and another form of encouragement, that œhe had consulted many ministers, and all concurred that he had not sinned the unpardonable sin. œRemember, he added, œthat Peter had not so many temptations to deny his Lord and Master as thou hast had, and yet he obtained mercy, and so mayst thou.

In passing, at the time when Islam in Europe was generally regarded as Antichristic and a mere religious sect, Satan-worshipping cult, heresy and deceit, forsaking Christianity and embracing Islam denoted the biggest and most unforgivable sin against Jesus Christ. Such was an act of religious betrayal and treason, and those who did it were called renegades (apostates and rebels). The practice greatly offended and frightened fellow Christians within the Muslim world and without it. Hence, notwithstanding his insincere conversion to Islam, Pitts was never at peace. He once replied to his father in heart-broken strain, œwishing that he had died as a child, that he might not have been the bringer of his parents grey hairs with sorrow to the ground.

Fortunately for Pitts his woes were soon to be mitigated somewhat. His third master was œan ancient and corpulent man, and of mild nature who treated him with great kindness. He treated him like his own son, and Pitts, in return, acknowledged that he had been a second parent to him. It was this benevolent master that took Pitts to Makkah and Madinah for hajj (pilgrimage). They came for the holy month of Ramadan, after which they stayed two months and ten days more until the commencement of the hajj season. In Makkah alone, they stayed about four months. After hajj, Pitts returned with his master to Algiers.

While in Makkah, Pitts received from his master a letter of freedom. The man was of advanced age and Pitts had expectations. However, œthough no longer a slave, the freedom of renegades was restricted, and had he been caught in the attempt to escape from Algiers, he would have been put to death with torture as an example. In spite of the peril, though, Pitts never stopped contemplating escape.

Then, œafter a lengthy period an opportunity of escape occurred. Some Algerine ships were despatched to Smyrna (modern-day Izmir) to assist the Turks, and Pitts was on one of them. Once in Smyrna, the escape plan got into gear and all the lingering doubts and hindrances, including psychological ones, were dispensed with. Ultimately, œafter waiting vainly for an English ship, he embarked, in European dress, on a French one. The ship safely reached Leghorn, and Pitts prostrated himself and kissed the earth. His homeward route lay through Germany.

Pitts escape took place between 1693 and 1694. He was 31 or 32 years old. In 1704 he published his story. It was titled œA True and Faithful Account of the Religion and Manners of the Mohammetans.

Pitts narrative accuracy

The first thing to be observed about Pitts book is that the author was relatively accurate in his narrations. Considering how inaccurate and prejudiced Ludovico di Varthemas and Vincent le Blancs accounts are, that was refreshingly new and pleasing. It was like a breath of fresh air. Without going over the top, though, Pitts work is still laden with bigotry and errors, but such is lot less conspicuous and primitive than the works of his predecessors. The problems associated with his work, likewise, seem to have been less purposeful and thought-out, too. They carried less venom.

Burton perfectly encapsulated Pitts relative intellectual integrity when he said: œHis description of these places is accurate in the main points, and though tainted with prejudice and bigotry, he is free from superstition and credulity.

Pitts was helped by the fact that he knew both Arabic and Turkish, at least colloquially. He spent in Algiers about fifteen years, which helped him acquire, intentionally or otherwise, a decent amount of knowledge concerning the religion and culture of Islam. His dramatic life experiences sufficed, despite the defects of his formal education, œto give fullness and finish to his observations.

That was a time when the Ottoman Turks dominated the Muslim political and cultural landscapes. They were the foremost torchbearers of Islamic civilisation. Algeria, like all countries of the Islamic west (al-maghrib al-Islami), was under the Ottoman rule. Arabic and Turkish were the lingua francas. Many people were bilingual, making Pitts case an image of the spectacle.

He, for example, repeatedly names Islamic religious rituals, traditions and occasions both in Turkish and Arabic. Some words are in pure Arabic, like beer el zemzem (the zamzam well), sallah (prayer) and hagar aswad (the black stone); others are in pure Turkish, like abdes (ablution), nomas or namaz (prayer), bayram (eid) and ekinde-nomas (Muslim third and middle prayer); and some words are Arabic loanwords, like erkaets (Arabic rakat, units of prayer), curban (Arabic qurban, sacrifice) and beat-Allah (Arabic baytullah, Kabah or the House of God).

Accuracy was Pitts aim. The title of his book says it all: œA True and Faithful Account of the Religion and Manners of the Mohammetans. The words œtrue and œfaithful were meant as much to bear witness as to invite and challenge. They connoted a burden. Not only his audience, but also his very self, did Pitts dare. If some of his non-Muslim European predecessors in Makkah and Madinah might have attempted to take advantage of the ignorance of the European audiences of the 16th and 17th centuries in relation to Islam and its holiest places, Pitts was different. He perceived it as a test and responsibility.

He felt duty-bound to accurately convey the truth to his poorly acquainted readership as much as possible. Thus, he was fond of reiterating in diverse contexts that he was an eye-witness, that he knew for sure, and that he spoke only what he knew. At one point he yet implores his audience to believe him, in connection with a false story, making the most of his self-proclaimed approach and intellectual rectitude. Ultimately, having described the hajj pilgrimage in Makkah and the worship closely connected with it, and before moving to the subject of Madinah, Pitts emphasised most emphatically that apart from doing all that faithfully and punctually, he was also ready to challenge the world to convict him of any known falsehood. The verdict was in the hands of readers.

Without a doubt, Pitts felt the presence and attention of his readers. He identified with them, feeling the weight of their needs and expectations. There was such a strong psychological and spiritual relationship uniting them. As if he was facing each and every one of them and was speaking most directly and most intimately to them. He addresses them as œyou, implying thereby that nothing stood between them, and between them collectively and the desired truth. He says, by way of illustration, œI shall now give you a more particular description of Mecca and the temple there, œI shall next give you some account of the temple of Mecca, œI shall now inform you how, when, and where, they receive the honourable title of Hagges, for which they are at all this pains and expense, and œI shall acquaint you with a passage of a Turk to me in the temple cloister.

Two reasons for Pitts accuracy

The reasons for Pitts comparative honesty and accuracy were two-fold. Firstly, he composed his book long after his ordeals. He had enough time to repeatedly look back at what had happened and to digest the events. There was little “ or perhaps absolutely nothing – to delight in. However, in hindsight, the final phases of his nightmare with his third but extremely compassionate and father-like master were the least painful. They may yet contained some faint elements of poignancy.

And it was during those phases that Pitts œperformed the hajj pilgrimage. His knowledge of Islamic faith and traditions was more than sufficient then; his mind was mature and amply sharp to enable him to make his observations precise and complete, and devoid of imprudence and of major fallacies; and finally, his depression and emotions of unbounded anger and hatred were rather stable and were no longer in charge of his thinking and behaviour.

Pitts left hajj and the holy cities of Makkah and Madinah with a strange impression. He was both fascinated as a human being and was sometimes hardened and at other times shaken as a de facto Christian. The experience rendered his mind additionally educated, plus more inquisitive than ever, and his total disposition aroused, startled, perplexed and amused – all at once. He left the places and the occasion with more questions than answers deep inside his soul. He at times might have become a torn personality. He praised and at the same time criticised certain aspects of both Islam and Christianity. From the very beginning he was hypercritical of Islam, but also subtly and not so subtly criticised Christianity. The subtle and not so subtle criticism of both religions tempts the reader to question Pitts true relationship with both of them.

Thus, having returned to England and having decided to share his story with his countrymen first and foremost, all that should have weighed heavily on Pitts. He must have felt indebted, to a certain degree, to his last merciful master who, after all, had granted him freedom, and must have felt attentive to the tensions of his turbulent emotional and spiritual state.

In other words, Pitts was indebted to the truth and nobody else. Revealing and sharing it was akin to settling all the debts, with others as well as with his own self. He needed to give in order to get, turning the efforts into the final juncture of his life-long quest for freedom. Once the goal and end of all ends, freedom suddenly became a means of the truth and an instrument of accountability.

It is worth mentioning that Pitts cordial relationship with his last master posed a temporary psychological barrier in his plans for escape. It functioned like the devil and was very busy tempting him to lay aside all thoughts of escaping, to return to Algier, and to continue his life as though a Muslim. Moreover, since he was now on the payroll “ having obtained freedom from his master – the loss of eight months pay and certain other monies seems to have been affecting his spirit. Eventually, however, the prospect of returning home as soon as possible and living out total freedom, proved irresistible.

The second reason for Pitts honesty and accuracy was related to an additional dimension of his social and moral responsibility. Once in Makkah he proclaimed: œI question whether there be a man now in England that has ever been at Mecca. Considering the life-story of the man, there was certainly nothing privileged in the involvement. However, things in the end developed into a responsibility, being indicative of a potential silver lining in the whole torment.

Knowing how poor and how poorly substantiated the Occident-Orient relationships were at the time, Pitts decided to seize the opportunity and contribute something to the bettering of the situation, giving thereby Christianity and Christians the edge over Islam and its followers. The initiative was in line with the famous method of Martin Luther (d. 1546) as to the effective ways of dealing with Islam and of proselytising Muslims, which at the time of Pitts composing of his book was supposed to be a well-known strategy.

According to the method, Christians should not be afraid at all of the base and absurd teachings of Islam as an Antichristic heresy and a Satan-worshipping sect. Instead of being defensive, they should be on the offensive. The more exposed and known the teachings and values of Islam are, the more easily will people understand their mendacities and absurdities, and the more easily will they reject them. The assertive truth is the best antidote for falsehood. It makes it recoil and retreat into the oblivion of its illusory realm. Just as the truth is self-evident, so is untruth.

In his preface to the first published Quran in Latin, Martin Luther thus wrote about the Quran as the source of everything Islamic: œI do not doubt that the more other pious and learned persons read these writings, the more the errors and the name of Muhammad will be refuted. For just as the folly, or rather madness, of the Jews is more easily observed once their hidden secrets have been brought out into the open, so once the book of Muhammad has been made public and thoroughly examined in all its parts, all pious persons will more easily comprehend the insanity and wiles of the devil and will be more easily able to refute them.

Pitts believed that the truth about the religion and manners of Muslims (Mohammetans) should be accurately written and proclaimed. There was no loss whatsoever entailed in the endeavour of exposing superstitions and delusions. There could only be gains. Let people read and learn about those things themselves before they are perhaps fooled by somebody else and based on some devious sources. And that is how the chief motive for writing Pitts book in the way it was written, was created. He owed it to himself, his people and his religion, placing it fully in the service of upholding the truth and extinguishing falsehood.

Pitts must have been taken aback by sight of an Irish renegade (a convert from Christianity to Islam) in Makkah, œwho was taken very young, insomuch that he had not only lost his Christian religion, but his native language also. This man had endured thirty years slavery in Spain, and in the French galleys, but was afterwards redeemed and came home to Algier. He was looked upon as a very pious man, and a great zealot, by the Turks, for his not turning from the Mahommedan faith, notwithstanding the great temptations he had so to do.

As Pitts was very much concerned œfor one of his countrymen who went home to his own country, but came again to Algier, and voluntarily, without the least force used towards him, became a Mahometan.

Examples of Pitts narrative accuracy

There are many instances where Pitts narrative accuracy comes to the fore. At times, it is virtually flawless.

For example, this is how he describes the arrival of his company in Makkah and the performance of ˜Umrah (lesser pilgrimage) before attending to anything else, including finding accommodation: œAs soon as we come to the town of Mecca, the Dilleel, or guide, carries us into the great street, which is in the midst of the town, and to which the temple joins. After the camels are laid down, he first directs us to the fountains, there to take abdes (ablution); which being done, he brings us to the temple, into which (having left our shoes with one who constantly attends to receive them) we enter at the door called Bab-al-salem, i.e. the Welcome Gate, or Gate of Peace. After a few paces entrance, the Dilleel makes a stand, and holds up his hands towards the Beat-Allah (it being in the middle of the Mosque), the Hagges imitating him, and saying after him the same words which he speaks. At the very first sight of the Beat-Allah, the Hagges melt into tears, then we are led up to it, still speaking after the Dilleel; then we are led round it seven times, and then make two Erkaets (a prayer of two units). This being done, we are led into the street again, where we are sometimes to run and sometimes to walk very quick with the Dilleel from one place of the street to the other, about a bowshot. After all this is done, we returned to the place in the street where we left our camels, with our provisions, and necessaries, and then look out for lodgings; where when we come, we disrobe and take of our Hirrawems (ihram as special pilgrim-garb), and put on our ordinary clothes again.

Having finally arrived at the place and for the occasion which pilgrims had been dreaming about their entire lives and for which as long they had been preparing themselves both physically and spiritually, everything had to be set aside for a moment. To pilgrims, that instant is as though – except for themselves and the Kabah (baytullah) and its holy mosque – nothing else exists, and as though the whole world has come to a halt. The moment must be captured, soaked up and savoured, however impossible a mission that might be. It must be engraved in the soul, the heart, the mind and the memory “ yet on the entire being. As such, it must be carefully guarded against the perpetual assaults of oblivion, obscurity and amnesia.

To do that, however, the best thing for a person to do is to make his own life and the entire life around him stand still, and to lose himself in the all-pervading aura of metaphysical purity and holiness. He moreover needs to rescind his self, his ego and his entire worldliness, and to submit completely to the mighty presence of the one and only existential greatness, supremacy and control.

That is why “ as Pitts observed the obvious – at the very first sight of the Kabah (baytullah), the pilgrims melt into tears. They never got back to their œnormal physical selves until the completion of hajj. If truth be told, many pilgrims never do. Such is the impact of hajj on most pilgrims that after hajj and after they return home, never are their lives the same again.

Next, about the rites of tawaf (circumambulation) around the Kabah and kissing the black stone (hajar aswad), Pitts says, highlighting not just the fervour and determination of pilgrims, but also their civility and moral qualities: œThis place is so much frequented by people going round it, that the place of the towoaf, i.e. the circuit which they take in going round it, is seldom void of people at any time of the day or night. Many will walk round till they are quite weary, then rest, and at it again; carefully remembering at the end of every seventh time to perform two Erkaets. Sometimes there are several hundreds at Towoaf at once, especially after Acshamnomas, or fourth time of service (sunset or evening prayer), which is after candle-lighting, and these both men and women, but the women walk on the outside the men, and the men nearest to the Beat. In so great a resort as this, it is not to be supposed that every individual person can come to kiss the (black) stone afore-mentioned; therefore, in such a case, the lifting up the hands towards it, smoothing down their faces, and using a short expression of devotion, as Allah-waick barick, i.e. Blessed God, or Allah cabor, i.e. Great God, some such like; and so passing by it till opportunity of kissing it offers, is thought sufficient. But when there are but few men at Towoaf, then the women get opportunity to kiss the said stone, and when they have gotten it, they close in with it as they come round, and walk round as quick as they can to come to it again, and keep possession of it for a considerable time. The men, when they see that the women have got the place, will be so civil as to pass by and give them leave to take their fill, as I may say in their Towoaf or walking round, during which they are using some formal expressions. When the women are at the stone, then it is esteemed a very rude and abominable thing to go near them, respecting the time and place.

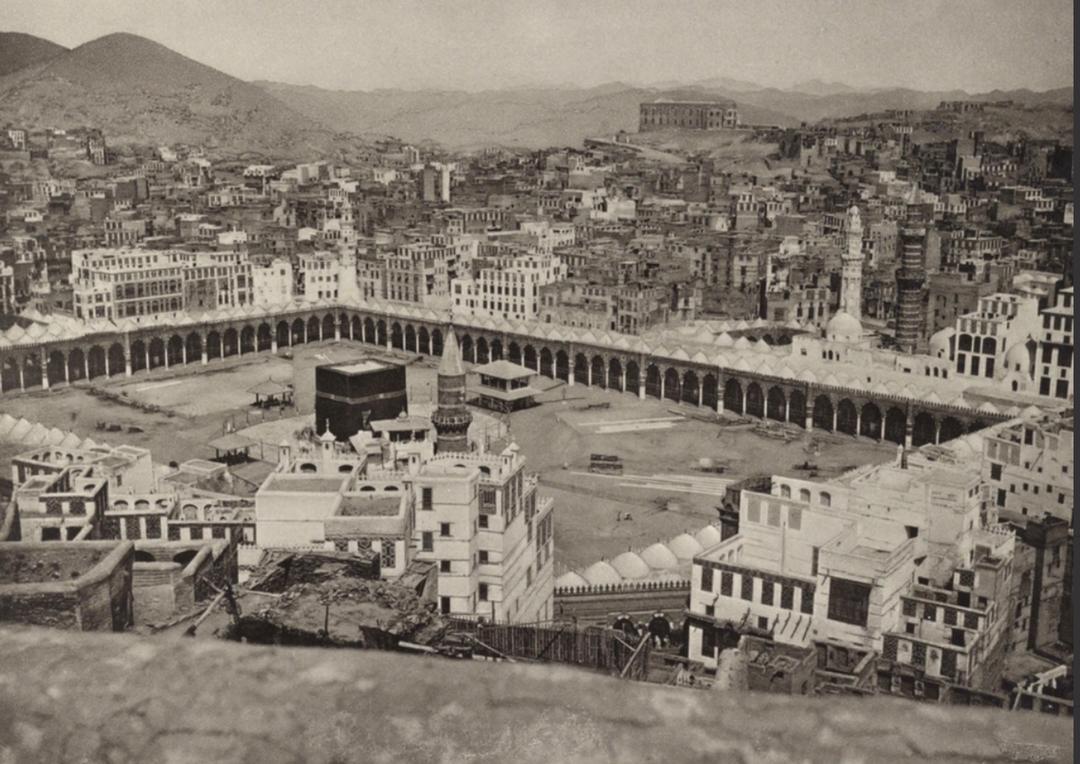

About the city of Makkah and its topography, Pitts states: œFirst, as to Mecca. It is a town situated in a barren place (about one days journey from the Red Sea) in a valley, or rather in the midst of many little hills. It is a place of no force, wanting both walls and gates. Its buildings are (as I said before) very ordinary, insomuch that it would be a place of no tolerable entertainment, were it not for the anniversary resort of so many thousand Hagges, or pilgrims, on whose coming the whole dependence of the town (in a manner) is; for many shops are scarcely open all the year besides. The people here, I observed, are a poor sort of people, very thin, lean, and swarthy. The town is surrounded for several miles with many thousands of little hills, which are very near one to the other. I have been on the top of some of them near Mecca, where I could see some miles about, yet was not able to see the farthest of the hills. They are all stony-rock and blackish, and pretty near of a bigness, appearing at a distance like cocks of hay, but all pointing towards Mecca.

Pitts then throws light on a superstition (œan odd and foolish sort of tradition) concerning the Makkah hills in particular and the hills of the whole world in general, and the ancient process of constructing the Kabah by prophet Ibrahim (Abraham). He says: œThe people here have an odd and foolish sort of tradition concerning them (hills), viz.: That when Abraham went about building the Beat-Allah, God by his wonderful providence did so order it, that every mountain in the world should contribute something to the building thereof; and accordingly everyone did send its proportion; though there is a mountain near Algier, which is called Corradog, i.e. Black Mountain; and the reason of its blackness, they say, is because it did not send any part of itself towards building the temple at Mecca.

Referring to two specific episodes from the history of Prophet Muhammads life and his prophet-hood mission, Pitts further writes: œThere is upon the top of one of them (hills) a cave, which they term Hira, i.e. Blessing; into which (they say) Mahomet did usually retire for his solitary devotions, meditations, and fastings; and here they believe he had a great part of the Alcoran brought him by the Angel Gabriel. I have been in this cave, and observed that it is not at all beautified; at which I admired. (Secondly,) about half a mile out of Mecca is a very steep hill, and there are stairs made to go to the top of it, where is a cupola, under which is a cloven rock; into this, they say, Mahomet, when very young, viz. about four years of age, was carried by the Angel Gabriel, who opened his breast, and took out his heart, from which he picked some black blood-specks, which was his original corruption; then put it into its place again, and afterwards closed up the part; and that during this operation Mahomet felt no pain. Into this very place I myself went, because the rest of my company did so, and performed some Erkaets, as they did.

After that, Pitts describes the Kabah as follows: œThe Beat-Allah, which stands in the middle of the temple, is four-square, about twenty-four paces each square, and near twenty-four foot (or paces, as commented by Burton) in height. It is built with great stone, all smooth, and plain, without the least bit of carved work on it. It is covered all over from top to bottom with a thick sort of silk. Above the middle part of the covering are embroidered all round letters of gold, the meaning of which I cannot well call to mind, but I think they were some devout expressions. Each letter is near two foot in length and two inches broad. Near the lower end of this Beat are large brass rings fastened into it, through which passeth a great cotton rope; and to this the lower end of the covering is tacked. The threshold of the door that belongs to the Beat is as high as a man can reach; and therefore when any person enter into it, a sort of ladder-stairs are brought for that purpose. The door is plated all over with silver and there is a covering hangs over it and reaches to the ground, which is kept turned up all the week, except Thursday night, and Friday. The said covering of the door is very thick embroidered with gold, insomuch that it weighs several score pounds. The top of the Beat is flat, beaten with lime and sand; and there is a long gutter, or spout, to carry off the water when it rains. This Beat-Allah is opened but two days in the space of six weeks, viz. one day for the men, and the next day for the women. As I was at Mecca about four months, I had the opportunity of entering into it twice; a reputed advantage, which many thousands of the Hagges have not met with, for those that come by land make no longer stay at Mecca than sixteen or seventeen days.

About the interior of the Kabah Pitts writes that it was extremely plain construction- and decoration-wise: œAnd I profess I found nothing worth seeing in it, only two wooden pillars in the midst, to keep up the roof, and a bar of iron fastened to them, on which hanged three or four silver lamps, which are, I suppose, but seldom, if ever, lighted. In one corner of the Beat is an iron or brass chain, I cannot tell which (for I made no use of it): the pilgrims just clap it about their necks in token of repentance. The floor of the Beat is marble, and so is the inside of the walls, on which there is written something in Arabic, which I had no time to read. The walls, though of marble on the inside, are hung over with silk, which is pulled off before the Hagges enter. Those that go into the Beat tarry there but a very little while, viz. scarce so much as half a quarter of an hour, because others wait for the same privilege; and while some go in, others are going out.

One of the most interesting things that Pitts correctly reports was the presence of the four maqamat or sites inside the holy mosque of Makkah for each of the four schools of Islamic jurisprudence (madhhab) and for their adherents to perform separately the five daily prayers. The maqamat assumed some elaborate and peculiar architectural qualities. Though inappropriate and inadvertently promoting, as well as deepening, disagreements, the phenomenon is portrayed by Pitts in a very reconciliatory manner, stressing that all Muslims, despite being divided into four œsorts (madhhabs), are united by fundamentals. Differences in the ceremonial part are negligible.

He explains: œOn each of the four squares of the Beat is a little room built, and over every one of them is a little chamber with windows all round it, in which chambers the Emaums (imams) (together with the Mezzins) perform Sallah, in the audience of all the people which are below. These four chambers are built one at each square of the Beat, by reason that there are four sorts of Mahometans. The first are called Hanifee; most of them are Turks. The second Schafee; whose manners and ways the Arabians follow. The third Hanbelee; of which there are but few. The fourth Malakee; of which there are those that live westward of Egypt, even to the Emperor of Moroccos country. These all agree in fundamentals, only there is some small difference between them in the ceremonial part.

In the context of the plain of, or mount, Arafat, Pitts, after duly describing its physical features, gracefully admits that he did not really understand the significance of the place and of the rites affiliated with it. That was so, most probably, owing to the fact that what goes on at Arafat during hajj, generally, is purely immaterial, exhilarating pilgrims and elevating them to the uppermost levels of spiritual realisation and essence. There is extremely little physical and outwardly that can be reminiscent of what transpires spiritually and inwardly. All that, apparently, evaded the interest, together with capacity, of Pitts, and he was honest about that. Persisting as a Christian, the spiritual depths of hajj “ and of Islam all together “ remained off-limits to him. He remained on the surface.

He writes: œThe Curbaen Byram, or the Feast of Sacrifice, follows two months and ten days after the Ramadan fast. The eighth day after the said two months they all enter into Hirrawem, i.e. put on their mortifying habit again, and in that manner go to a certain hill called Gibbel el Orphat (El Arafat), i.e. the Mountain of Knowledge; for there, they say, Adam first found and knew his wife Eve. This Gibbel or hill is not so big as to contain the vast multitudes which resort thither; for it is said by them, that there meet no less than 70,000 souls every year, in the ninth day after the two months after Ramadan; and if it happen that in any year there be wanting some of that number, God, they say, will supply the deficiency by so many angels. I do confess the number of Hagges I saw at this mountain was very great; nevertheless, I cannot think they could amount to so many as 70,000. There are certain bound-stones placed round the Gibbel, in the plain, to show how far the sacred ground (as they esteem it) extends; and many are so zealous as to come and pitch their tents within these bounds, sometime before the hour of paying their devotion here comes, waiting for it. But why they so solemnly approach this mountain beyond any other place, and receive from hence the title of Hagges, I confess I do not more fully understand than what I have already said.

Pitts then explains almost impeccably the ritual of throwing pebbles, which takes place at the Mina site: œThe next morning they move to a place called Mina, or Muna. It is about two or three miles from Mecca. Here they all pitch their tents (it being in a spacious plain), and spend the time of Curbaen Byram (eid al-adha), viz. three days. As soon as their tents are pitched, and all things orderly disposed, every individual Hagge, the first day, goes and throws seven of the small stones, which they had gathered, against a small pillar, or little square stone building. Which action of theirs is intended to testify their defiance of the devil and his deeds; for they at the same time pronounce the following words, viz. Erzum le Shetane wazbehe; i.e. stone the devil, and them that please him. And there are two other of the like pillars, which are situated near one another; at each of which (I mean all three), the second day, they throw seven stones; and the same they do the third day. You must observe, that after they have thrown the seven stones on the first day (the country people having brought great flocks of sheep to be sold), every one buys a sheep and sacrifices it; some of which they give to their friends, some to the poor which come out of Mecca and the country adjacent, very ragged poor, and the rest they eat themselves; after which they shave their heads, throw off Hirrawem, and put on other clothes, and then salute one another with a kiss, saying, ˜Byram Mabarick Ela, i.e. the feast be a blessing to you. These three days of Byram (eid) they spend festively, rejoicing with abundance of illuminations all night, shooting of guns, and fireworks flying in the air; for they reckon that all their sins are now done away, and they shall, when they die, go directly to heaven.

Finally, concerning the city of Madinah and the Prophets tomb in the citys holy mosque (the Prophets mosque), Pitts as precisely narrates: œMedina is but a little town, and poor, yet it is walled round, and hath in it a great Mosque, but nothing near so big as the temple at Mecca. In one corner of the Mosque is a place, built about fourteen or fifteen paces square. About this place are great windows, fenced with brass grates. In the inside it is decked with some lamps, and ornaments. It is arched all over head. In the middle of this place is the tomb of Mahomet (where his corpse is laid) which hath silk curtains all around it like a bed; which curtains are not costly nor beautiful. There is nothing of his tomb to be seen by any, by reason of the curtains round it, nor are any of the Hagges permitted to enter there. None go in but the Eunuchs, who keep watch over it, and they only light the lamps, which burn there by night, and to sweep and cleanse the place. All the privilege the Hagges have, is only to thrust in their hands at the windows, between the brass grates, and to petition¦

At this juncture, Pitts dismisses two misunderstandings: firstly, that there were no less than 3,000 lamps around the Prophets tomb; œbut that is a mistake, for there are not, as I verily believe, an hundred; and I speak what I know, and have been an eye-witness of.

Secondly, like his predecessors, Pitts discloses that it was storied by some people “ definitely in Europe – that the Prophets coffin was hung up by the attractive virtue of a loadstone to the roof of his mosque and that it remained suspended there. He then categorically rejects the myth: œBut believe me it is a false story. When I looked through the brass gate, I saw as much as any of the Hagges; and the top of the curtains, which covered the tomb, were not half so high as the roof or arch, so that it is impossible his coffin should be hanging there. I never heard the Mahometans say anything like it.

Pitts even brings up an Islamic belief according to which Jesus Christ will ultimately be buried near Prophet Muhammads grave within the same chamber. He elaborates the belief with an astonishing precision and impartiality. He says: œOn the outside of this place, where Mahomets tomb is, are some sepulchres of their reputed saints; among which is one prepared for Jesus Christ, when he shall come again personally into the world; for they hold that Christ will come again in the flesh, forty years before the end of the world, to confirm the Mahometan faith, and say likewise, that our Saviour was not crucified in person, but in effigy, or one like him.

Enduring errors and elements of bias

Despite everything, nonetheless, Pitts was still a 17th and 18th-century European Christian. That means that even if he sincerely wanted, he could not completely free himself from the sway of the continents popular views and misconceptions about Islam, Muslims and Islamic culture. The sentiment was intrinsically negative and was sustained by the uneasy and mendacious relationships of the day between Christendom and Islamdom. There was a long way to go before the outlooks started to get better.

Pitts was caught in the crossfire. Once confronted with the realities of the Muslim world, it was impossible for him to dissociate himself from everything he had hitherto learned and had known about it; as it was hard to aptly comprehend, as well as trust, his new knowledge and experiences. While at the same time neither his status and his overall personal circumstance, nor the majority of external factors, proved conducive to him. As if at times, literally, everything worked against him. He was scarcely presented with an opportunity to truly dissect, contemplate and harmonise what was going on. The hajj episode, in part, was the only opportunity, and it inevitably produced some intriguing results.

As a consequence, Pitts was a confused personality. His feelings towards Islam and Muslims were dominated by hate and contempt, but were occasionally impressed with quantities of genuine curiosity and appreciation. Hence, some people ended up questioning how honest – or otherwise “ he was towards both his ostensible Islam and his actual Christianity. From time to time, he might yet have stood at a crossroads. At any rate, as far as Islam is concerned, Pitts can be best described as an unsettled and agnostic bigot. His book clearly exudes that spirit, making it a comparative breakthrough in the evolution of the medieval and early modern European-Christian literature on Islam and Islamic culture.

The following are examples of Pitts glaring errors and prejudices, which he perpetrated while reporting about hajj. In doing so, he oscillated between supporting Christian anti-Islamic apologetics and polemics, and endorsing outright narrow-mindedness.

First, Pitts underlines that he œgave no credit to the Muslim belief that prophet Ibrahim (Abraham) built the Kabah. Like most things Islamic, that too was a fantasy.

Second, Pitts calls the holy mosque of Makkah (al-masjid al-haram) œtemple, Friday œMuslim Sabbath, Islamic beliefs and traditions œsuperstitions and delusions, and Muslims œpoor (lowly and pitiable), blind and idolatrous.

Third, he calls Prophet Muhammad a œbloody impostor and a œjuggler (magician) whom pilgrims petition (make a request to him).

Fourth, Pitts erroneously says that the black stone (hajar aswad) was formerly white and was called œHaggar Essaed, i.e. the White Stone. œBut by reason of the sins of the multitudes of people who kiss it, it became black, and is now called Haggar Esswaed, or the Black Stone.

Fifth, Pitts amazingly contends that the Kabah is in effect the object of Muslims devotion, œthe idol which they adore: for, let them be never so far distant from it, East, West, North, or South of it, they will be sure to bow down towards it; but when they are at the Beat (bayt, from baytullah, the Kabah), they may go on which side they please and pay their Sallah towards it. In any case, there can hardly be a better repudiation of this error than what Burton has said concerning it: œNothing more blindly prejudiced than this statement. Moslems turn towards Meccah, as Christians towards Jerusalem.

Sixth, Pitts mistakes the maqam Ibrahim (the stone upon which prophet Ibrahim stood, or which served him for a scaffold, when he was building the Kabah) for the sepulchre or grave of Ibrahim. The sepulchre stood near the Kabah – about twelve paces away “ œenclosed within iron gates. It is made somewhat like the tombstones which people of fashion have among us, but with a very handsome embroidered covering. Into this persons are apt to gaze.

Seventh, Pitts claims that Muslims esteem their holy water, zamzam, as superstitiously œas the papists do theirs.

Eighth, to Pitts, prophet Ibrahim was instructed to offer up his second son Ishaq (Isaac) and not his first son Ismail (Ishmael).

Ninth, Pitts regards Sufi dhikr (remembrance of God) sessions in the vicinity of the Kabah as œa pretty play enough for children.

Tenth, Pitts writes that in terms of uncleanliness Makkah was awful and was equal to Grand Cairo. It likewise came œshort of none for lewdness and debauchery; and they will steal even in the temple (al-masjid al-haram) itself.

Impressed by Muslim piety and zeal

Another aspect of Pitts story that stands out is his fascination with Muslim piety and zeal demonstrated throughout the hajj ceremony. The feelings were real and he hesitated neither to suppress, nor communicate, them, during the hajj and later when he was composing his travelogue. He confesses that he himself could not hold back his tears at what he was witnessing. That happened as soon as he together with other pilgrims reached Makkah and started performing the initial acts of worship.

The pilgrims wept almost inconsolably at the very first sight of the Kabah. The situation continued relentlessly all the way through. œAnd I profess, Pitts writes, œI could not choose but admire to see those poor creatures so extraordinary devout, and affectionate, when they were about these superstitions, and with what awe and trembling they were possessed; in so much that I could scarce forbear shedding of tears, to see their zeal, though blind and idolatrous.

Pitts appeared to be unable to strike the right balance between his beliefs that Muslims were deluded, false, irrationally superstitious and idolaters, and between the actual events. He subtly wonders if the public uncontrollable outpouring of the most sincere emotions he had ever seen could be associable with untruth, deviation and malevolence. As if he furthermore wonders if the genuine was compatible with the false, and the purported with the established set of realities. He certainly knew the answers but did not want, nor was he ready, to be confronted with the implications of their profound nature. The best thing, therefore, was not to dwell extensively on the matter and to ignore it, just like many other obstinate heads before and after him, dismissing it as an aberration, foolishness and a form of demonic possession.

Pitts reserved some of his most poignant expressions for describing the extraordinary situation at Arafat, which is the quintessence of the whole hajj ceremony. Its experience, correspondingly, epitomises the whole experience of hajj. He writes: œIt was a sight indeed, able to pierce ones heart, to behold so many thousands in their garments of humility and mortification, with their naked heads, and cheeks watered with tears; and to hear their grievous sighs and sobs, begging earnestly for the remission of their sins, promising newness of life, using a form of penitential expressions, and thus continuing for the space of four or five hours.

Surprisingly, at that point Pitts even saw appropriate to take aim at his Christian coreligionists, deploring the religious apathy of many of them, which became all the more evident now after being juxtaposed with the Muslim extraordinary devoutness and passion. He states that œit is matter of sorrowful reflection, to compare the indifference of many Christians with this zeal of these poor blind Mahometans, who will, it is to be feared, rise up in judgment against them and condemn them.

Based on this assertion, and the one before where he snapped at some superstitious customs of the papists, it can be deduced that Pitts was an ardent follower of the Reformation, albeit the one spearheaded by the Church of England. At the heart of all reformatory movements stood the criticism of the spiritual degeneration as much among popes and their clergy as among the ordinary people. Parenthetically, the word œpapist and its derivatives such as œpapism date back to the Protestant Reformation. œThese and related terms such as ˜popish and ˜popery are still sometimes used by Protestants to show contempt for Roman Catholic practices and tenets.

When conversing about the Kabah, Pitts explains that its top is flat, beaten with lime and sand. There is a long gutter, or spout, to carry off the water when it rains. And when it does, pilgrims will run, throng and struggle, to get under the said spout, and so that the water that comes off the Kabah may fall upon them, œaccounting it as the dew of Heaven, and looking on it as a great happiness to have it drop upon them. But if they can recover some of this water to drink, they esteem it to be yet a much greater happiness.

Moreover, the author draws attention to the aftermath of the opening of the Kabah and peoples visit to its interior. He says when all that was over, the ruler of Makkah, who was Sharif, embarked on cleaning the place himself on account of his piety and humbleness. He did so with some of his companions. And first of all, they washed the interior with the holy water, zamzam, and after that with sweet water. œThe stairs which were brought to enter in at the door of the Beat being removed, the people crowd under the door to receive on them the sweepings of the said water. And the besoms wherewith the Beat is cleansed are broken in pieces, and thrown out amongst the mob; and he that gets a small stick or twig of it, keeps it as a sacred relic.

Pitts also mentions that he was reminded by a pilgrim that lying on the back close to the Kabah with the feet towards it, is an irreverent posture; that turning ones back towards the Kabah when one in the end takes leave of it is also disrespectful; that people did not think it lawful to buy anything till they have completed their hajj and have received the title of hajji; that people kissed the camels that bore the kiswah (cover for the Kabah) that was manufactured in Egypt and transported to Makkah yearly; that there were masters of learning inside al-masjid al-haram who, while presiding in high chairs over large clusters of people, daily expounded out of the Quran (that is, conducted religious classes); that people performed their daily prayers with strict punctuality and discipline; that people paid a visit to the Prophets tomb with a wonderful deal of reverence, affection and zeal.

One of the final non-prescribed acts performed by pilgrims before leaving Makkah perfectly exemplifies the total account of piety and zeal. Every one buys a shroud (kaffan) of fine linen to be buried in (œfor no coffins are used for that purpose). The shroud could be procured elsewhere, including Pitts Algier, and at a much cheaper rate, but they chose to buy in Makkah œbecause they have the advantage of dipping it in the holy water, Zem Zem. They are very careful to carry the said kaffan with them wherever they travel, whether by sea or land, that they may be sure to be buried therein.

Due to all this, Pitts was not disposed to discredit any extremity in relation to the articulated examples of Muslim devotion. It appeared as though everything was somehow possible. He says for example that some authors had written that many pilgrims after they had returned home, have been so austere to themselves as to pore a long time over red-hot bricks, or ingots of iron, and by that means willingly lose their sight, œdesiring to see nothing evil or profane, after so sacred a sight as the temple at Mecca. However, to be fair to Pitts, about this particular implausibility he admits that he œnever knew any such thing done. It was too extreme “ hence, unacceptable “ even for the most fervent Muslims.

Finally, about the reverence for the zamzam water, and how that sentiment extended beyond the precincts of hajj and the city of Makkah, rendering it at once a universal and perpetual ethos, Pitts says: œYea, such a high esteem they have for it (zamzam), that many Hagges carry it home to their respective countries in little latten or tin pots; and present it to their friends, half a spoonful, may be, to each, who receive it in the hollow of their hand with great care and abundance of thanks, sipping a little of it, and bestowing the rest on their faces and naked heads; at the same time holding up their hands, and desiring of God that they also may be so happy and prosperous as to go on pilgrimage to Mecca. The reason of their putting such a high value upon the water of this well, is because (as they say) it is the place where Ishmael was laid by his mother Hagar. I have heard them tell the story exactly as it is recorded in the 21st chapter of Genesis; and they say, that in the very place where the child paddled with his feet, the water flowed out.

Conclusion

Since his young age, Pitts was obsessed with travel and fancied thrill-seeking adventures. However, never in his wildest dreams did he get even close to what life had in store for him. His life story had it all, not just in terms of conventional travel and exploration, but also in terms of existential import and self-discovery. Even though he was not elevated to the status of a bona fide legend, yet his case personified an age and its spirit. He went through the school of hard knocks to make a name for himself in history. He immortalised himself as much by sharing his narrative with the world, as by doing so with a relative accuracy. Nevertheless, such was the state of the 17th and 18th-century European inter-religious consciousness that Pitts neither could nor wanted to fully steer clear of prevalent misconceptions, prejudices and factual errors. On the whole, his book titled œA True and Faithful Account of the Religion and Manners of the Mohammetans typified a relative breakthrough in the evolution of the medieval and early modern European-Christian literature on Islam and Islamic culture.***