By Spahic Omer

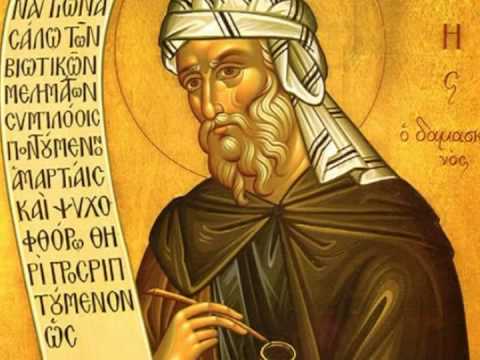

John of Damascus (675-749) was a Christian monk, priest and scholar. He was born and educated in Damascus, the centre of the Umayyad establishment. He belonged to a prominent Damascene Christian family.

In Damascus he was employed as a civil servant, just as his father Sarjun and grandfather Mansur had been before him. He most probably occupied a high position as a tax official. The family served the Islamic government during the first two exemplary generations of Islamic civilisation: sahabah (companions) and tabiun (followers or successors).

It is noteworthy that for quite a long time Greek was widely used in the bureaucracy of the Umayyad state and many positions were filled with non-Arabs and non-Muslims. For some, the government apparatus of the Umayyads was never fully Arabized.

According to Daniel Janosik, œin the early stages of the Arab takeover of Syria, the Arabs were more tolerant than even the Byzantine emperor Heraclius, and they usually retained the existing administrative structure as well as the official Greek language.

After some time, however, perhaps in 706, John left his governmental post and the city of Damascus to become a priest and monk at a monastery near Jerusalem. Some believe that he did so because the newly appointed caliph, al-Walid b. ˜Abd al-Malik, embarked on a significant Islamisation of his administration (making it œmore thoroughly Muslim) (Andrew Louth).

John died at his monastery in Jerusalem at the time when the Umayyad Caliphate was crumbling and the Abbasids were taking over the reins.

Most importantly, John was a pioneer in Christian apologetics and polemics against Islam. For several centuries, he and his views played the role of an influencer on the Christian polemic and apologetic attitudes. His insights are featured in his œHeresies (the Heresy of Ishmaelites) and œDisputation between a Christian and a Saracen.

The following are four observations on his polemics and apologetics, concentrating on these issues: Muslims as Saracens, Ishmaelites and Agarenes; summary of John of Damascus views on Islam; Islam as yet another heresy; questioning the knowledge and truthfulness of John of Damascus.

Muslims as Saracens, Ishmaelites and Agarenes

John was a standard-setter in systematic Christian-Muslim polemics, so much so that he could be regarded as its father. Essentially, every subsequent Christian polemicist, as well as apologist, owed a debt of gratitude to him, one way or another.

He was also the first who officially named Muslims œSaracens, œIshmaelites and œAgarenes, except that the œSaracens appellation might have been used earlier, albeit colloquially.

All those names were pejorative and were meant to deride Muslims right from the start and at the level of fundamentals. They were aimed to spur peoples imagination and to facilitate, along with cement, the projection of Muslims as the religious and civilisational œother.

John said that Muslims were called Ishmaelites because they descended from Ishmael, who was born to Abraham of Agar. They were thus destined to take a subordinate position to the line of Isaac as another son of Abraham, who was one of the three patriarchs of the Israelites and the grandfather of the twelve tribes of Israel. His son was Jacob, later named Israel.

Accordingly, the reputation of Ishmael was never illustrious. The Bible says about him: œHe shall be a wild donkey of a man, his hand against everyone and everyones hand against him (Genesis, 16:12). The word œIshmael later became synonymous with œsocial outcast and pariah, for Ishmael and his mother Agar (Hagar) were cast out by Abraham and Sarah at the behest of the latter.

It follows that Muslims as a nation epitomised the spirit of Ishmael, the father of Arabs and, by extension, Muslims. It is said in the commentary of the above biblical verse that Ishmael, just as prophesied, lived in œa wilderness, delighting in hunting and killing wild beasts, and robbing and plundering all that pass by; and such an one Ishmael was¦ And such the Saracens, his posterity, were, and such the wild Arabs are to this day, who descended from him.

John further said that because of Ishmaels mother, Agar, Muslims were also called Agarenes, in association with Abrahams œslave woman, Agar or Hagar. It is generally held that some early Muslims (especially Arabs) preferred to be called œSaracens rather than œ(H)agarenes because of the connection of the former with Abrahams œfree wife Sarah. The name sounded less disagreeable.

However, John still managed to put a distasteful spin on the matter when he said in his introduction to the œHeresy of Ishmaelites: œThey are also called Saracens, which is derived from Sarras kenoi, or destitute of Sarah, because of what Agar said to the angel: ˜Sarah hath sent me away destitute (empty).

Indeed, labelling, alienating and deliberately placing obstacles between Islam and Christianity, and between Muslims and Christians, was unbecoming from John. In no way was such a thing beneficial and conducive, and was ready to generate more harm than benefit. He knew more than anybody else who he lived and was dealing with.

œIslam and œMuslims were heavenly titles and signified the core not only of a religious and cultural, but also existential, identity. Muslims did not invent them. Therefore, to articulate anything else, especially with an affronting disposition, was a sign of resentment, artificial ignorance and prejudice. It served the interests of a hidden agenda, to which, unfortunately, John was not immune and was not exempt from.

Allah says about that in the Quran: œSurely the (true) religion with Allah is Islam (Alu ˜Imran, 19).

œHe has chosen you and has not placed upon you in the religion any difficulty. (It is) the religion of your father, Abraham. Allah named you œMuslims before (in former scriptures) and in this (revelation) that the Messenger may be a witness over you and you may be witnesses over the people (al-Hajj, 78).

In passing, everyone can become a member of the universal community of Muslims and can join the universal orb of Islam as a total code of life. There is nothing discriminatory, nor intolerant, in the two designations. There is only openness and invitation to broad-mindedness and dialogue. There is a bona fide hope and optimism. Only such as harbour prejudiced tendencies have problems with the notions of œIslam and œMuslims.

Needless to say that all prophets preached Islam (the truth), were Muslims, and those who followed them were Muslims too (i.e., followers of Islam as the only revealed truth). This includes Moses and Jesus as well and all of their genuine followers. To follow Islam means to subscribe to the absolute and only ontological reality, and to be Muslim means to remain true to the intrinsic self and to the Creator and His divine model intended for life.

That Johns inappropriate naming of Muslims was a deliberate attempt to emphasise the œotherness of Islam as a religion and Muslims as a nation and its followers, could be corroborated by the fact that Muslims were generally called either Muslims or Arabs during his time. John deviated from the culture and initiated a new one – for the reasons explained above.

For example, Anastasius of Sinai (died after 700), a Christian scholar, priest and monk, referred to Muslims as Arabs. He was one of Johns sources for his own works, although there is no direct mention made therein to Anastasius brief references to Muslims as Arabs and their doctrines (Peter Schadler).

Summary of John of Damascus views on Islam

Johns views on Islam and Muslims were seminal. At the same time, they were surprisingly disrespectful and somewhat aggressive. They served as a precursor to what could be dubbed a radical and antagonistic anti-Islamic polemics, which in turn paved the way for the emergence of the embryonic forms of what is called at the present time Islamophobia.

John wrote that Islam was a mere superstition and a form of deviation. It was a forerunner of the Antichrist. Muhammad was a false prophet who, after having chanced upon the Old and New Testaments and likewise, it seems, having conversed with an Arian monk, devised his own heresy. œThen, having insinuated himself into the good graces of the people by a show of seeming piety, he gave out that a certain book had been sent down to him from heaven. He had set down some ridiculous compositions in this book of his and he gave it to them as an object of veneration.

He called the Islamic pivotal concept of tawhid (Gods Oneness) and the entire Islamic creed concerning Jesus and his mother Mary œabsurd things and worthy of laughter œin this book (Quran) which he (Muhammad) boasts was sent down to him from God.

He alleged that the Quran states that Mary was the sister of Moses and Aaron “ an allegation perennially repeated afterwards by most Christian polemicists, including Riccoldo da Monte di Croce (d. 1320) and Nicholas of Cusa (d. 1464).

John likewise poked fun at the ways Prophet Muhammad received his revelation, in particular when in the state of sleep. He said: œAnd they answer that, while he was asleep the Scripture came down upon him. And we say to them in jest that, since he received the Scripture while sleeping and did not have a sense of the activity it is in him that the folk proverb (œyou are spinning me dreams) was fulfilled.

He called Muslims – again sarcastically – œmutilators of God. This is because Muslims, like Christians, believe that Christ is the Word and Spirit of God, but consider both the Word and Spirit to be outside of God, in which case “ as John understood – God is without Word and Spirit. œThus, having avoided making associates to God you have mutilated Him. For it would be better for you to say that he has an associate than to mutilate him as if he were a stone, or wood, or to introduce him as some other inanimate object. So while you falsely call us Associators, we call you mutilators of God.

John furthermore imputed to Muslims that they rub themselves against a (black) stone (al-hajar al-aswad) at their Kabah in Makkah, and that they worship the stone by kissing it. That is because œupon it Abraham had intercourse with Hagar, or œbecause on it he tied the camel when he was about to sacrifice Isaac.

John then presented the real reason for such a repulsive tradition. œThis, then, which they call ˜stone, is the head of Aphrodite, whom they used to venerate (idolise and worship) and whom they called Khaber, upon which, even now, one who looks carefully can see on it traces of a carving.

To John, that was a covert manner whereby (many) Muslims continued their idol-worship. To make sure things were consistent throughout, not by chance did he mention at the beginning of his œHeresy of Ishmaelites that Muslims were a people who worshiped and venerated the morning star and goddess Aphrodite, œwhom they themselves called (K)Habar in their own language, which means ˜great.

After that, John partially mentioned, distorted and falsified several verses and accounts of the Quran, calling them follies, lies and obscenities. He portrayed Muhammad as a liar, phoney, adulterous, charlatan and sexual maniac. The Quranic reports are to be seen merely as œfoolish tales worthy of laughter which, because of their number, I think it necessary to pass over.

Finally, to depict Muhammad as a legislator as well, who through a series of laws fortified his total at once theological and sacramental deviation from the œold ways, John without any elaboration concluded his treatise on the heresy of Ishmaelites by saying: œHaving made a law that they and the women be circumcised, he also commanded (them) neither to observe the Sabbath, nor to be baptised, and to eat things forbidden by the Law but, on the other hand, to abstain from other things which the law permits. He also forbade the drinking of wine completely.

John had a strong reason for doing this in the said fashion. In that way, the confirmation of the œotherness of Islam and Muslims was complete. Making no comments whatsoever on the Islamic laws mentioned, John left it to every individual to make a judgment for himself. Things entailed in the Islamic law and the Quran are silly and irrational in the extreme. As such, they are also self-explanatory. So, therefore, just insinuating the obvious and underlining the glaring disparities with the œscriptural mainstream is worth a thousand words of commentary.

Islam as yet another heresy

John of Damascus was a time when heresies were raging and were afflicting the core of Christian doctrines and sacraments. John stood at the heart of the developments. He dedicated his life to diagnosing and annihilating them, to such an extent that the Second Council of Nicaea – exactly 38 years after Johns death, in 787 – was convened to resolve the issue of iconoclasm (a movement that opposed the veneration of icons). John was a proponent of iconography, producing at least three books to support it. His books and his scholarly views played a big role during the Council and in issuing a declaration of faith concerning the restoration of the veneration of icons.

That was the last of the first seven ecumenical Councils of the Church. It should likewise be mentioned that the sixth Council, or the Third Council of Constantinople, was held in 680-681, when John was five years old. This Council tackled the heresies of monoenergism (believing that Christ had only one energy) and monothelitism (believing that Christ had two natures but only one will).

And the worst was yet to come in 1054: the East-West, or Great, Schism, which connoted the culmination of theological and political differences between Eastern and Western Christianity.

John thus enthusiastically wrote in the introduction of his œThe Fount of Knowledge: œThen next, after this, I shall set forth in order the absurdities of the heresies hated of God, so that by recognising the lie we may more closely follow the truth. Then, with Gods help and by His grace I shall expose the truth – that truth which destroys deceit and puts falsehood to flight and which, as with golden fringes, has been embellished and adorned by the sayings of the divinely inspired prophets, the divinely taught fishermen, and the Godbearing shepherds and teachers.

The result of this crusade was Johns remarkable work titled œThe Fount of Knowledge, a portion of which expounds heresies. He outlined them as 100 heresies. The heresy of Islam (Ishmaelites) is the 100th. He concluded his exposition thus: œAlthough they amount to but a hundred altogether, all the rest (other heresies) come from them.

Interestingly, at the beginning of his discussion, John does not mention Islam. He writes, instead, that the parents and archetypes of all heresies are four in number, namely Barbarism (from Adam to Noah), Scythism (from Noah to the building of the Tower of Babel and a few years after the Tower period), Hellenism and Judaism. œOut of these came all the rest “ indirectly counting Islam.

Only at the end of all the heresies the world had witnessed, was Islam and the heresy of Ishmaelites mentioned. Such was not by accident. As a heresy, John mentioned Islam as though an appendix, or even a finale. Islam was not only a heresy; it was much more than that. It was the climax of all heresies, and of all evil.

In its capacity as a heresy, John identified Islam with Arianism, which denied the divinity of Christ. It held that Jesus was created by God and hence, was neither coeternal nor consubstantial with him. The main advocate of this opinion was the Alexandrian priest Arius (d. 336). That was denounced as a heresy by the Council of Nicaea in 325, which was the first ecumenical Council of the Church.

John, therefore, contended that Muhammad did not devise his heresy until after he had come across the Old and New Testaments and after he had met and conversed with an Arian monk in Syria. The monk taught Muhammad about the created-ness and non-divinity of Jesus, the view which they both shared.

Parenthetically, the monk in question must be Bahira who, nevertheless, was a Nestorian Christian. He, in equal measure, might have been a Mandaean, belonging to Mandaeism (Sabaeanism or Sabiiyyah) and subscribing to a monotheistic and gnostic religion. Bahira indeed is narrated to have met Muhammad during one of the latters trips to Syria when he was a young boy, and is said to have recognised in him a prophet-hood sign.

As absurd as it is unscrupulous, this charge was primed to persist through ages, in the end evolving into the idea that Islam is nothing but a plagiarised religion. For one, Martin Luther (d. 1546) adopted and upgraded the scheme. Echoing the similar spirit, he wrote in his book œOn the war against the Turks that Islam is a plagiarised religion patched together out of œthe faith of Jews, Christians and heathen (pagans and idolaters).

At any rate, Islam came after Christianity, after all prophecies and hopes of mankind had been fulfilled. What remains “ forming the essence of Christian eschatology – is the second coming of Jesus œin glory to judge the living and the dead and his kingdom will have no end (Nicene Creed).

Thus, anyone who denied or opposed the roles of Christ, imposing himself and his ideas on him and his own teachings and ideas, is not solely a heretic, but as well an impostor, a false spiritualist and a forerunner of the Antichrist. Such a one tends to undermine and destroy the complete edifice of Christian theological beliefs and thought. Without a doubt, there can be nothing noble that could be associated with those enterprises and their protagonists.

To John, Prophet Muhammad was all of those. In short, he was evil incarnate. His peril was more complex and hence, more challenging, as proven by the recurring historical events to which John himself was able to attest.

While perceiving Islam as a heresy – yet somewhat a separate one from the rest of heterodoxies – John suggested that Islam, in addition, was satanic, heathen, apocalyptical (a portent of the apocalypse as envisaged by the Scriptures), and it feigned to have altered salvation history, which is another fundamental in Christian theology.

Consequently, Islam as a perennial threat should be condemned both in theory and practice and should be utterly rejected. It furthermore should be approached as a whole and as a comprehensive system of thought and life. Such an outlook should be reflected in the ways Christians are supposed to communicate, deal and interact with Muslims, never regarding them as thorough allies and equal partners.

It is safe to assert that those ideals inevitably contributed to the forming of edgy relationships between Christians and Muslims throughout within the Islamic state and beyond. It created a prejudiced and opinionated Christian mentality, and erected a series of obstacles between the two sides. A wall of mistrust was rising fast.

Johns views certainly mattered in the continuous forging of domestic, together with international, Christian-Muslim relations, leaving little room for genuine dialogue, understanding and cooperation. Yet sheer coexistence, based on sincerity and acceptance, was at stake. The presence of Islam and Muslims signified a necessary evil.

This type of thinking was additionally responsible for engendering the hostile and biased Christian polemics against essentially everything Islamic. It was also an indirect cause of the Crusades and later Islamophobia, as concepts and historical as well as civilisational phenomena.

No wonder that Islam, soon after Johns time, came to be viewed almost universally within the Christian intellectual and theological circles œas a product of a conniving false prophet and son of Satan named Muhammad. In fact, he was considered “ at least metaphorically – to be the first born son of Satan, for he and his minions were all instrumental figures in the soon approaching apocalypse whereby God would in the end crush the Devil and his work and bring about an end to all of his enemies – Islam being one of the greatest (Adam S. Francisco).

Besides, there were other practical reasons “ and benefits – for regarding Islam as a heresy. Some revolved around the preservation of the Christian faith and the identity of Christians in the midst of any heretical group through the processes of self-identification and self-differentiation. Doing so in the midst of Muslims was of particular importance considering that ever more Christian territories were coming under the Muslim rule.

By labelling the Ishmaelites as partakers of ˜heresy, a whole body of church law could potentially be applied to them, further facilitating the modes of dealing with them on a daily basis (Peter Schadler). This way, undoubtedly, the œus versus them dialectics, in the name of religion and its spiritual realisation, was set to intensify and be sustained for a very long time. The better Christian a person was, the more alienated from Muslims he became.

Questioning the knowledge and truthfulness of John of Damascus

John of Damascus was a prominent religious leader and authority. He was a paragon and also trend-setter of Christian polemics. However, it is startling how thoughtless, insensitive and imprudent he was in relation to his thought on Islam and Muslims. His views clearly verged on intellectual mediocrity and even out-and-out ignorance. His predilection for bias, prejudgments and aversion are discernible too.

That is astounding beyond all reason, for he was well-educated; was familiar with Arabic; held a post in the Islamic government which was open to interreligious dialogue and debates; lived and interacted his entire life with Muslims; witnessed the religion of Islam all around him in thought, word and practice; and “ above all else – one of his motivations was to participate in comparative religion and to defend the truth.

That said, Johns scant and flawed knowledge of Islam, whence his equally flawed and dishonest judgements stemmed, was inexcusable. He set a bad example, which was followed by most subsequent Christian polemicists. His thought and methods were used for centuries after he died.

Such rendered the image of Islam, Muslims and Islamic civilisation in the tradition of Christian polemics highly inaccurate and prejudiced. The bias and detestation were so carefully crafted and guarded that not even the current age of enlightenment and information can tear them down. The modern Christian polemics fares no better than its earliest exemplars.

Daniel Janosik tried to give good reason for the problematic and inconsistent – or at best peculiar – elements in Johns polemical thought. He tried to defend the indefensible and justify the unjustifiable, so he had to swerve from one extremity to another. He said: œIt may be that during the first half of the eighth century the religion that was to become Islam was still in its formative process, and the rules, the traditions and the Quran may still have been developing as the Arabs absorbed more and more land, money and power. Thus, Islam was not very distinct from Christianity in the time of John of Damascus and it is only in the latter half of the eighth century, when the earliest biographies on Muhammad were being written and the first hadiths were being penned, that the finalisation of the Quran was also taking place and the distinctions were becoming sharper and more defined, both in a theological and a cultural sense.

Daniel Janosik then added, quoting Andrew Louth, that œIslam was not fully formed by the time of the death of Muhammad in 632, but was, in part, a reaction to the success of the Arab conquest of the Middle East in the 630s and 640s. From a movement inspired by apocalyptic Judaism, emerging Islam distinguished and separated itself from Judaism, and found its identity in the revelations made to Muhammad. The development of the religion took some decades, and only towards the end of the seventh century did something recognisable as Islam emerge. Johns account, if written about the turn of the century, would fit with such a picture.

It seems that neither John nor a great many contemporary Christian authors were able to distinguish between Islam as revealed to Prophet Muhammad – which was accomplished and fully operational before the Prophets death – and what later came to be known as various interpretations of Islam, Islamic thought, Islamic sciences, etc. They looked at the history of Islam and its civilisation through the prism of the history and development – yet evolution – of Christianity.

If John only wanted, he could have easily checked and learned anything about Islam, either directly from the Quran or by asking a Muslim scholar or an imam in a mosque. All of these would have proved as much effortless as effective, bearing in mind the notable social and religious profile of John, and the conduciveness of conditions in the Muslim Damascus and Jerusalem. As a matter of fact, so common and straightforward were the majority of issues John had dealt with and had misrepresented, that most average Muslims on the street could have significantly enlightened him about them.

Nonetheless, taking pains to thoroughly examine and find the truth about Islam was not a priority for John. Christianity was the benchmark. Whatever conflicted with it and could not fit inside its encoded patterns, had to be conveniently rejected. Heresies and any other forms and degrees of unorthodoxy deserved neither consideration nor appreciation. The latter is pre-empted by witch-hunts of selves and identities, recognising no role of reason and actual experience.

Islam was wrong and rejected, not because it was intellectually and empirically false, but simply because it was not part of Christianity – yet it opposed it. Muslims furthermore were wrong and evil, not because they were realistically so, but simply because they belonged to and followed Islam.

John was so blinded by his œfanatical affiliation with Christianity that he could not see, nor appreciate in any way, anything beyond it. He viewed the world but in terms of Christianity “ unreasonably and obsessively held as the truth “ and its relationship with the rest “ likewise unreasonably and obsessively held as forms of falsehood. Christianity was right just because it was his and he followed it, while the rest were wrong just because they resided in the realm of œothers and were œdifferent. This understanding, it goes without saying, was bigotry at its best.

For example, John dismissed Prophet Muhammad as a phony and impostor, firstly, because he did not conform to the prophet-hood paradigm of the Bible, and secondly, because he defied his personal religious standards (preferences). He accused him “ based on his own theological constructs, as well as sheer ignorance – of being a disciple of an Arian, that he performed no miracles, and that he was not prophesied by earlier prophets mentioned in the Bible.

Similarly, Muhammad was a poor legislator and his laws were worthless, purely because they contravened certain religio-cultural models relating to the laws of the Bible, rather than because they might have been irrational or were proven impractical. Hence, for instance, John criticised the fact that Muslim men are circumcised (even though the Old Testament “ unlike the New Testament – commands it) and that Muslims were asked not to keep the Sabbath (even though the Sabbath as a Jewish biblical tradition was later abandoned by Christians themselves). John yet had a problem with the verity that Muhammad œabsolutely forbade the drinking of wine.

The thing is that John “ and many others “ overlooked that Islam takes Christians to task, principally, over the absurdity, together with unacceptability, of the divinity and son-ship of Jesus; for corrupting and distorting Jesus original legacy “ including the scripture revealed to him as a prophet of Almighty God, which was called Injil; for the lack of authenticity and legitimacy with reference to their existing scriptures; and for all their misconduct associated with the deformation “ intentional or otherwise “ of the true legacy of Jesus and the invention of a bogus one.

Most of those charges applied to the formative and murkiest periods of the evolution of the Christian faith, when it evolved from the mere and œindigenous Jewish sphere to a full-fledged universal religion, and when the pure truth became lost, or misrepresented at best. Many alternatives, both approximate and distant, emerged as potential candidates for the right and throne of the truth.

At first, there was no Christianity. What came to be called Christianity was a theological construct that eventually prevailed over the rest of competing alternatives. That is why the concept and occurrence of heresies featured prominently in the formation of Christianity, and featured permanently ever since throughout its critical developmental phases. The main role of the ecumenical Councils was to guard and sustain the established religious construct (Christian orthodoxy). A majority of constructs were subjective and expedient, though, with no objective historical existence.

Those who speak in the name of Christianity and defend it, do so in the name of a chosen ideological construct. John was not an exception. His declared war against heresies was tantamount to a war against other constructs (competing ideas and ideologies) that might have threatened his own. He did not defend Christianity per se; rather, he defended a selected “ and dominant – form of it, often resorting to extreme hermeneutical principles and methods. The net result of such an approach was his bigotry and narrow-mindedness. Had he embarked on his declared mission solely for the sake of affirming the true religion, propagated by the true Jesus and in the true holy scriptures, his outlook would have been much different.

And that was a main reason why John did not bother to really understand Islam and Muslims, why he detested them, and why, at the end of the day, he could never have been at the same wavelength as them. When it comes to the case of Christianity, Muslims are more concerned about the universals and the absolute certainty of the truth, while Christians are more interested in the particulars and the particular theorisations of the truth. The Muslim primary focus is the total and overarching framework, while the Christian focus is the controlled and subjective readings of issues. One can easily sense this mind-set at work especially in Johns œDisputation between a Christian and a Saracen.

At long last, it is amazing to discover that almost all contemporary Christian polemicists and apologists still resort to most of the anti-Islamic theological nonsenses John had used about thirteen centuries ago. That only underscores how much they have œprogressed and how œrich their arsenals – when it comes to dealing with and repudiating Islam “ are. It also shows how unserious they are with regard to properly understanding Islam and Muslims in the globalised world, and with regard to paving the way for constructive dialogues and for forging better partnerships in such world.***